How to Charge

Atlas/Maps/Demand Curve Growth MOC

- Your pricing structure is how you charge for your products or services. We’ll cover the five most common and effective ones below. Once we’ve gone over them, we’ll give you guidance on how to select the model that makes the most sense for your business.

- Since pricing for physical products is pretty obvious, we’ll just briefly touch on it. With a few exceptions—e.g., consumables like monthly coffee delivery—physical products charge per product.

- The focus here is on pricing for intangible products/services, so if you’re in the physical-product realm, you can probably skip ahead to the next page.

- Two rules of thumb when it comes to pricing structure:

- Keep your pricing simple. There’s a reason why tiered pricing usually has a max of four tiers—more than that could overwhelm the buyer. ==Don’t add friction to the buying process by making the conversion point too complex.==

- Don’t innovate for the sake of being different. If your industry has a standard pricing structure, you could introduce friction if you try something totally different. If an innovative revenue model is a core part of your business concept, then your pricing will look different from most. But most startups don’t need to invent a new model—at least not at this stage. Instead of focusing on innovation, ==aim for efficiency, low risk, and high growth potential.==

# Pricing structures

- Below are five standard pricing structures. As you’ll see, there can be overlaps between them.

- Note: We don’t include freemium here because we think of it as ==part of a product and acquisition strategy, not a revenue model.== It’s a way to acquire and convert customers, but it’s outside the scope of how and what they pay for (i.e., a pricing model). We’ll go over freemium later, in “Pricing: Bonus Tactics."

| Pricing Structure | What it is | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usage-based | Charging for customers’ use of or transactions with your product | - Companies that use value metrics typically double their growth rate vs. flat-fee or feature-based tier pricing - Aligns your pricing with your value props—and what your customers get value from - Low friction—initial cost to the user is low | - Requires significant data - Risky if you get it wrong - Potential taxi-meter effect - Can make revenue projection less predictable |

| Tiered | Multiple pricing tiers | - Often much simpler to start with than non-tiered usage-based pricing (needs less data) - Encourages upgrading once a user is hooked in the product but reaches the limit of their tier - Effective way to highlight a rich feature set | - Compared to non-tiered usage-based pricing, less revenue potential - Could introduce friction by requiring a tier decision at purchase - Different tiers’ perceived values are set against each other |

| Flat-rate | One price per product/service for all buyers | - Simplicity - Transparency—easy to communicate - Avoids “subscription fatigue” | - Doesn’t factor in cohorts or personas - Can have high initial friction, e.g., if there’s a sizable upfront cost |

| Per-user | A subscription type that charges per user or seat | - Simplicity, for low friction - Transparency - Revenue projection is more predictable than with usage-based pricing | - If separate seats don’t add value to the end user, per-user pricing isn’t aligned with product value—which could mean reduced revenue and lower conversion rates - Doesn’t factor in cohorts or personas - Seats can get shared |

| Variable | Pricing that varies depending on factors like buyer-seller negotiations | - Flexibility, especially if your costs are variable per customer | - Lack of transparency - Adds complexity to your sales team’s job, and adds to their workload - Risk of inefficiency |

# Usage-based pricing

- What it is: Charging for customers’ use of or transactions with your product. ==The more a customer uses it, the more they pay.==

- Usage-based pricing is considered ==the gold standard for startups.== It uses your value metric and therefore has the most direct connection between a product’s value and its price.

- It can be a type of subscription, but isn’t always.

- Who it’s for: OpenView Partners did a survey of about 600 SaaS companies in 2021, and they found that 45% had usage-based pricing—up from 34% in 2020. It’s increasingly becoming the SaaS true standard, in addition to being the gold standard.

- Usage-based pricing is especially effective for products that have ==built-in stickiness and repeatable, consistent usage.== Customers wouldn’t one-and-done a business like Square, so it makes sense for them to charge per transaction.

- Although we recommend a usage-based approach generally, it doesn’t always make the most sense for startups. ==If your startup is very young, you might not have enough data to know the value of your metric.== You might need to start out with a different structure (you can always switch over).

- We’ll get into metric value more in How Much to Charge, and we’ll go over how to get data in the project for this module. But for now, here are two hypotheticals of what we mean by ==insufficient data==:

- Few client relationships: Your food-delivery app launched a month ago. You only have a handful of restaurant partners, so you have little data on what they’re willing to pay per transaction. You decide to charge a fixed monthly fee for now, until you’ve collected more data about what partners are willing to pay and how much they think your service is worth.

- Limited client understanding: Your collaboration platform launched half a year ago, but you don’t have a clear sense yet of who your actual customers are. You’re still relying on pre-launch best-guess buyer personas. Until you’ve analyzed your real buyers and gathered specific insights about the features they value most and how much they value them, you might need a different structure, like per-user pricing.

- If you do have a lot of data, you’ll face another challenge: analyzing it. ==Usage-based pricing requires data science.== It’s not enough to know what your value metric is. You also have to know:

- What it’s worth

- Often, what it’s worth by segment

- How to forecast it based on consumption, possibly amid high variability

- So although we recommend usage-based pricing, ==we don’t recommend jumping into it without resources.== Make sure you have the data and data analytics to know not only that it’s right for your business, but that you know your metric’s worth.

- Examples of usage-based pricing:

- Mailchimp—price is based on the number of contacts. This is a subscription usage-based structure, with users paying monthly.

- Zapier—price is based on the number of “tasks.” Another monthly subscription.

- Amazon Web Services—AWS has “pay-as-you-go” pricing. Charges are based on which services you use and how long you use them. An example of non-subscription usage-based pricing.

- Postmates—price is based on orders (unless you sign up for a flat-fee monthly membership)

- The Barcelona comedy club that charges per laugh

- Pros:

- As mentioned earlier, companies that use value metrics typically double their growth rate vs. flat-fee or strictly feature-based tier pricing

- Aligns your pricing with your value props—and what your customers get value from

- Low friction—initial cost to the user is low

- Cons:

- Requires significant data and customer learnings

- Risky if you get it wrong

- Potential taxi-meter effect

- Can make revenue projection less predictable

# Tiered-pricing

- What it is: Multiple pricing tiers. The pricier the tier, the more the customer gets.

- There’s plenty of overlap between tiered and usage-based pricing.

- Examples include Netflix (three tiers, with more screens the higher you go), Shopify Payments (three tiers, with lower credit card rates and transaction fees the higher you go), and Evernote (three tiers, with more storage the higher you go).

- Tiers can also have feature upgrades or a combination of usage-based pricing and feature upgrades.

- Who it’s for: Tiered pricing is often used for SaaS, but it can also be used for physical products, such as different tiers for different combinations or quantities of subscription products.

- Examples of tiered pricing:

- Spotify Premium—four tiers with more features as you move from an individual to a family plan (with a lower-cost student plan)

- Peloton membership—two tiers, standard and all-access, with different features. All-access is only available to Peloton equipment owners.

- LinkedIn Premium—four plans based on different goals: Career, Business, Sales Navigator Professional, and Recruiter Lite

- Pros:

- Often much simpler to start with than non-tiered usage-based pricing. Needs less data and fewer customer learning insights.

- Encourages upgrading once a user is hooked into the product but reaches the limit of their tier

- Effective way to highlight a rich feature set

- Cons:

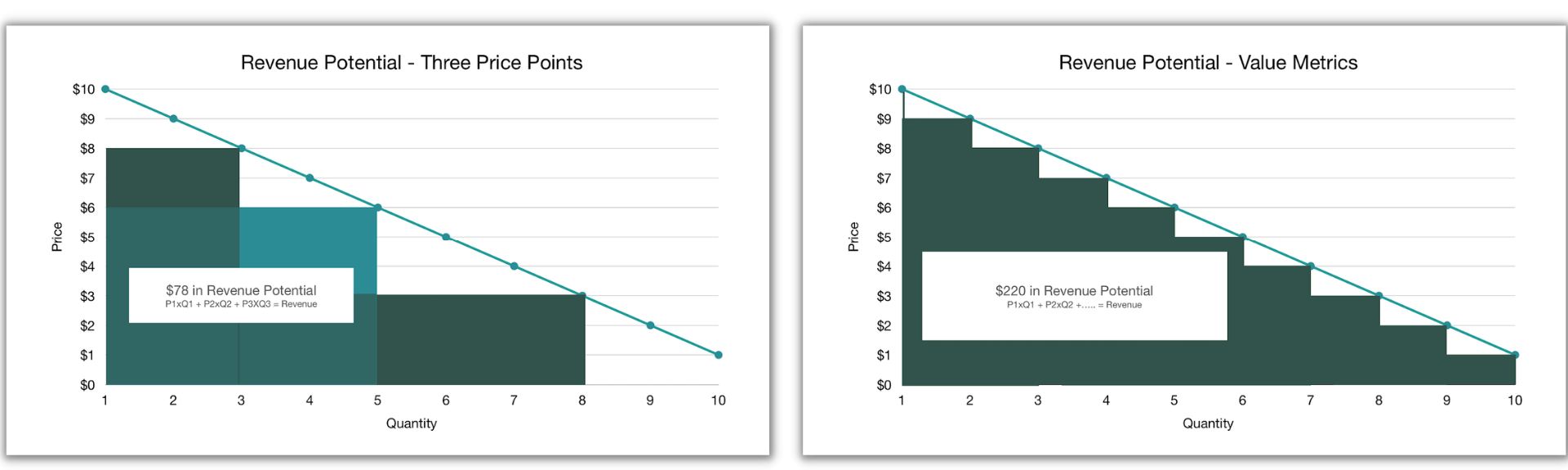

- Compared to non-tiered usage-based pricing, you’re missing out on revenue potential. Patrick Campbell, the CEO of ProfitWell, represents this graphically:

- Could introduce friction by requiring a decision at the purchase conversion point (which is why one tier is often “recommended”)

- Your different tiers’ perceived values are being set against each other.

- Compared to non-tiered usage-based pricing, you’re missing out on revenue potential. Patrick Campbell, the CEO of ProfitWell, represents this graphically:

# Flat-rate pricing

- What it is: One price per product/service for all buyers

- Flat-rate pricing can take a few different forms.

- It can be a one-time payment—typically paid upfront, as with ecommerce.

- Or it can be a subscription type with a single rate instead of different tiers. Every subscriber pays the same every month/year as every other subscriber.

- Who it’s for: One-time upfront payments work ==when the majority of value is realized and delivered immediately upon purchase==, or ==when value isn’t distributed equally and consistently over time.==

- A flat-rate subscription can work ==if all your buyer personas share a comparable willingness to pay== (more on that on the next page), or ==if you have only one or two personas.==

- Because of its simplicity, and because it doesn’t require a ton of customer data, ==flat-rate pricing can be an attractive option for early-stage startups.==

- Examples of flat-rate pricing:

- Strava—there’s one subscription plan for everyone (plus a freemium option)

- Demand Curve—students pay once upfront and then don’t have any subsequent fees

- Bon Appetit—other than some discount options (e.g., for students and educators), everyone pays the same amount for a digital + print subscription

- Pretty much all retail ecommerce

- Pros:

- Simplicity

- Transparency—easy to communicate and market

- Avoids ==“subscription fatigue”== (as one Redditor put it, “I want services, yes. But, I don’t need them every month. And, if I do, I want to out-right buy the product. Not be told I have to pay $x.xx a month for it.”)

- Cons:

- Doesn’t factor in cohorts or personas. Every user pays the same, although needs can vary widely.

- Can have high initial friction if there’s a sizable upfront cost (especially for new companies that don’t have brand recognition yet and are entering competitive verticals)

# Per-user pricing

- What it is: A subscription type that charges per user or seat

- Who it’s for: Often used in SaaS, especially for team-based and enterprise products

- Per-user pricing works best ==when individual seats offer unique value.== Logging in to one account provides a different experience from logging in to another. Maybe the data you’re accessing is different, or maybe the experience is tailored to your specific habits or needs.

- Examples of tool types that offer unique value for different seats:

- A B2B tool for managing sales leads, pipelines, etc. One salesperson’s pipeline will look different from another’s, so it makes sense for them to have separate seats.

- A tool with individual user profiles or histories (such as work/activity history)

- Software that handles private information. Users shouldn’t share their logins.

- A collaboration/communication platform with network effects—meaning that everyone gets more value from the product when more team members use it

- Another use case for per-user pricing: When you can’t find a strong value metric or proxy, ==charging by user can be a decent alternative to usage-based pricing.==

- Real-world examples of per-user pricing:

- Donut—four tiers based on the number of users. Tier 1 is for 1-24 users, Tier 4 is for 100+.

- Salesforce—four tiers: Essential, Sales Professional, Service Professional, and Pardot Growth. Each charges per user per month.

- Gusto—four B2B tiers with per-user pricing for each, plus a contractor-only plan

- Auth0—B2C and B2B plans are based on monthly active users

- As you can see, per-user pricing is often used in conjunction with another structure—typically either tiered or usage-based pricing. If you’re going to implement per-user pricing, that’s what we recommend: ==pairing it with another structure.==

- Per-user + tiered: Per-user pricing can have its own form of taxi-meter effect. Charging by tier instead of individual user makes the “more users, more money” concept less salient.

- Per-user + usage-based: One way to combine per-user and usage-based pricing is by charging for active users instead of all users—so customers are getting more value with more use (and so they don’t have to pay for inactive seats). Another way is with add-ons. You could either 1) have usage-based core pricing with add-ons per number of users, or 2) have per-user core pricing with feature add-ons.

- Pros:

- Simplicity, for low friction

- Transparency—also a friction reducer

- Revenue projection is more predictable than with usage-based pricing, and pricing is more predictable for customers

- Cons:

- If separate seats don’t add value to the end user, per-user pricing isn’t aligned with product value. This can lead to reduced revenue and lower conversion rates, since companies won’t see the value in paying for additional seats.

- Doesn’t factor in cohorts or personas. Every user pays the same, although needs can vary widely.

- Seats can get shared

# Variable pricing

- What it is: Pricing that varies

- In SaaS and B2B, variable pricing often takes the form of a ==“contact us” CTA on a company’s pricing page==, instead of a listed price. Prices are ==negotiated on a per-customer basis.== It’s principally used for enterprise customers.

- Variable pricing isn’t the same thing as dynamic pricing, which is when prices change based on market demand (like Uber surge pricing). We’ll discuss dynamic pricing in “Pricing: Bonus Tactics.”

- Who it’s for: Enterprise B2B, high-value products and services. Variable pricing is a good option if you have variable costs in your client relationships. For example, if you know that a customer will require extensive onboarding and relationship management, you can negotiate a higher price with them. If you’re building custom software for a client, or if they require more of your team’s time or resources than others, it makes sense to give them a custom rate.

- Examples of variable pricing:

- ClickUp—five tiers (including a freemium plan) with a “contact sales” CTA for the highest

- Notion—four tiers, from Personal to Enterprise. Signing up for Enterprise requires contacting sales.

- Agencies that negotiate contracts for unique deliverables with individual clients

- Pros:

- Flexibility, especially if your costs are variable per customer

- Cons:

- Lack of transparency

- Adds complexity to your sales team’s job, and adds to their workload

- Risk of inefficiency, e.g., if building custom deals produces lower net profit than offering non-custom deals would, or if the time it takes your team to build those deals is lower ROI than other activities