How Much to Charge

Atlas/Maps/Demand Curve Growth MOC

- The last part of pricing strategy is the most salient: your actual price.

- There are three standard methodologies for finding it:

- Value-based — price is based on the value your product creates for customers

- Cost-plus — price is based on the costs of making your product plus its profit margin

- Competitor-based — price is based on how your competitors are pricing

- ==These aren’t mutually exclusive==—you can use a combination of two or all three. In fact, it’s best not to overlook any of them entirely. After all, you should never exceed your costs, ignore your competitors, or disregard the value your customers place in your product.

- Your price won’t be perfect. Pricing isn’t an exact science. As Patrick Campbell puts it, it’s ==a “doubt elimination process.”== That’s why we recommend revisiting and optimizing it every quarter.

| Pricing method | What is it | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value-based | Pricing based on the perceived value of your product | - Most data-driven method - Puts your customers first - Most directly tied to JTBD - Can result in a more customer-focused product roadmap - Best way to avoid underpricing - Allows your pricing to evolve with your product | - Requires a lot of data - Not an exact science—it’s impossible to calculate exactly what customers perceive your product value to be |

| Cost-plus | Pricing based on your costs and profit margin | - Quick and easy—just requires a simple calculation | - Doesn’t factor in customers’ needs, expectations, or views of your product, for limited growth potential - Tendency to underestimate costs - Tendency to undervalue your product, for lost revenue potential |

| Competitor-based | Pricing based on competitors’ prices | - Low effort—just look at what your competitors are charging - Keeps your product aligned with the market - Low risk—you’re unlikely to make a drastically wrong pricing decision | - Doesn’t factor in customers’ needs, expectations, or views of your product - Your competitors might not be doing it right - You’re not your competitors. If your product is more valuable than what’s on the market, simply copying competitors’ pricing means lost revenue potential. |

# Pricing methodologies

# Value-based pricing

- What it is: pricing based on perceived product value

- Value-based pricing is generally the pricing methodology we recommend. For the same reason that we recommend a usage-based structure: ==It directly ties your product’s price to its JTBD and the value customers get from it.==

- As with usage-based structure, value-based pricing uses your value metric. If your value metric is videos, you would do market research and collect data to find out how much each video should cost.

- That cost depends on your customer base’s ==willingness to pay.==

- Willingness to pay:

- the ==maximum price== customers are willing to pay for your product.

- It’s a function of factors including:

- Demand. Demand is in turn influenced by seasonality, supply (whether there’s a surplus or shortage), trends, and economic conditions.

- Perceived value—how much customers believe your product is worth. Perceived value also has various moving parts, including: the pricing and appeal of competitors/alternatives, how exclusive your product is, your brand perception, product quality, value props and positioning, and celebrity/influencer endorsements. It’s also affected by how much your product makes or saves users, how much it addresses pain points, and how urgently it addresses them.

- Personas. Willingness to pay can vary widely by cohort, which is one of the reasons why it’s so important to have customer personas. A customer with more disposable income (more buying power) might be willing to pay more. Age, gender, risk tolerance, and personal hobbies can all influence willingness to pay.

- Getting willingness to pay wrong can be the beginning of the end for a startup.

- For example, Juicero notoriously charged $699 for a juicer that, a Bloomberg report found, took just as long to squeeze juice as manual juice-squeezing took. Customers weren’t willing to pay that much.

- Despite raising $118 million in funding, the company folded within 16 months.

- Who it’s for: We recommend value-based pricing for most companies. It’s the best methodology—if you have the resources for it.

- But not all startups will. Collecting and analyzing data for value-based pricing takes time. It takes having customers or prospects to talk to. ==Early-stage startups in particular might need to start with a simpler pricing methodology==, like a combination of cost-plus and competitor-based, then move toward value-based as their business matures.

- Pros:

- Most data-driven method with the least amount of guesswork

- Puts the customer first

- Most directly tied to JTBD and the value your customers get

- Can result in a more customer-focused product roadmap—e.g., if you add features based on what customers want (and want to pay for)

- Best way to avoid underpricing

- Allows your pricing to evolve with your product

- Cons:

- Requires a lot of data—not a con per se, but can be a setback. Finding out what customers think your product is worth can be a resource- and time-intensive process.

- Not an exact science—you won’t be able to calculate your product’s precise perceived value. Close enough has to be good enough.

# Cost-plus pricing

- What it is: pricing based on your costs and profit margin

- Cost-plus pricing is the ==lowest-effort way to set a price==, since it doesn’t entail any customer or competitor research.

- All it takes is a formula: price = costs + target profit margin

- So if your product costs $50 to make (including all labor, overhead, and material costs) and you want to earn a 100% profit margin on it, you would calculate $50 + (100% of $50). Your price would be $100.

- Who it’s for: Cost-plus is often used for physical products like food and clothes.

- Ecommerce retailer Everlane, for example, shows the costs that go into their denim, and how their price results from those costs plus markup

- Cost-plus pricing can be useful for any early-stage startup, especially in combination with competitor-based pricing. But to scale their growth, mature SaaS companies should take a more value-based approach.

- Pro:

- Quick and easy—just requires a simple calculation

- Cons:

- Doesn’t factor in customers’ needs, expectations, or views of your product, which probably means growth potential isn’t fully realized. Your customers might be willing to pay more than you’re charging.

- Tendency to underestimate costs

- Tendency to undervalue your product, leaving revenue on the table

# Competitor-based pricing

- What it is: pricing based on competitors’ prices

- Competitor-based pricing is straightforward. You look at what your competitors are charging, then set your price based on your findings.

- Who it’s for: It’s beneficial for any startup at any stage to know what their competitors are charging, as a benchmark if nothing else. If you’re entering—or in—a highly competitive vertical (e.g., many consumer product goods), or one in which price plays a large role in purchase conversion, competitor-based pricing will be especially useful.

- But in general, it’s best as a ==supplement to other pricing methods==, not as a sole price determiner. Pros:

- Low effort—just look at your competitors’ prices

- Keeps your product aligned with the market

- Low risk—your price might not be optimal, but you’re unlikely to make a drastically wrong pricing decision Cons:

- Doesn’t factor in customers’ needs, expectations, or views of your product, for limited growth potential

- Your competitors might not be doing it right

- You’re not your competitors. If your product is more valuable than what’s currently on the market, you’ll lose revenue potential if you simply copy competitors’ pricing.

# Project: Find your price

- Based on the above explanations, choose the pricing methodology (or combination of methodologies) that’s most appropriate for your startup. Use the following steps to implement it.

- Even if value-based pricing isn’t right for your startup—or right for it now—we recommend collecting willingness-to-pay data. It will be important as you scale and optimize.

- To do this, we’ll use a method called the Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter.

# Value-based pricing

- The Van Westendorp method, introduced by Dutch economist Peter van Westendorp in 1976, is a ==useful technique for collecting and analyzing willingness-to-pay data.== You can use it whether you’re sending out a survey or conducting customer interviews.

- For now, we’ll go over the questions to ask. We’ll get into how to distribute those questions and analyze your results later in this module, on the page “Project: Pricing Market Research.”

- But we do want to give a heads up here: The analysis stage isn’t a simple process. It takes Excel formulas and a graph with multiple curves. You might need to set aside a few hours to go through the process. ( Here it is, in case you’d like a preview.)

- Here are the two steps for asking Van Westendorp questions:

- As part of your survey or interview “script,” introduce your product. Describe what it does. Explain what customers get for what they pay for, but don’t include the actual price.

- Then ask these four questions:

- At what price would you consider the product to be so expensive that you would never consider buying it?

- At what price would you consider the product to be starting to get expensive, but you’d still consider buying it?

- At what price would you consider the product to be a good deal—a bargain?

- At what price would you consider the product to be so cheap that you’d question its quality?

- Be sure to specify the currency. If your product has a subscription, also add a time interval to each question, e.g., “at what monthly price…” This will ensure that the data you’re collecting is for a consistent time frame.

# Cost-based pricing

- To do cost-plus pricing, use the simple formula price = costs + target profit margin.

- What should your target profit margin be? The answer to that question is very ==industry-dependent.== A coffee shop’s profit margin will be much lower than a SaaS enterprise’s. Not only can SaaS enterprise charge more, but they might have fewer daily expenses, like equipment and storefront rent.

- We recommend researching your industry’s standard profit margin by looking at resources like industry news and reports. Aswath Damodaran, an NYU professor of corporate finance and valuation, has a helpful breakdown of margins by sector.

- Tip: We mentioned earlier that one of the cons of cost-plus pricing is the tendency to underestimate costs. To avoid this risk, make sure you factor in all the costs of producing your product or service (e.g., overhead, salaries, tools, etc.).

# Competitor-based pricing

- Competitor-based pricing research will be easy for you, since you’ve already gone through the Competitor Research module.

- Revisit the research you did then. Do a deeper dive on ==competitors’ pricing strategies==: what they charge for, how they charge, how much they charge.

- Look at ==market feedback== on their prices. Do any customer reviews comment on their pricing, calling it either too high or surprisingly low?

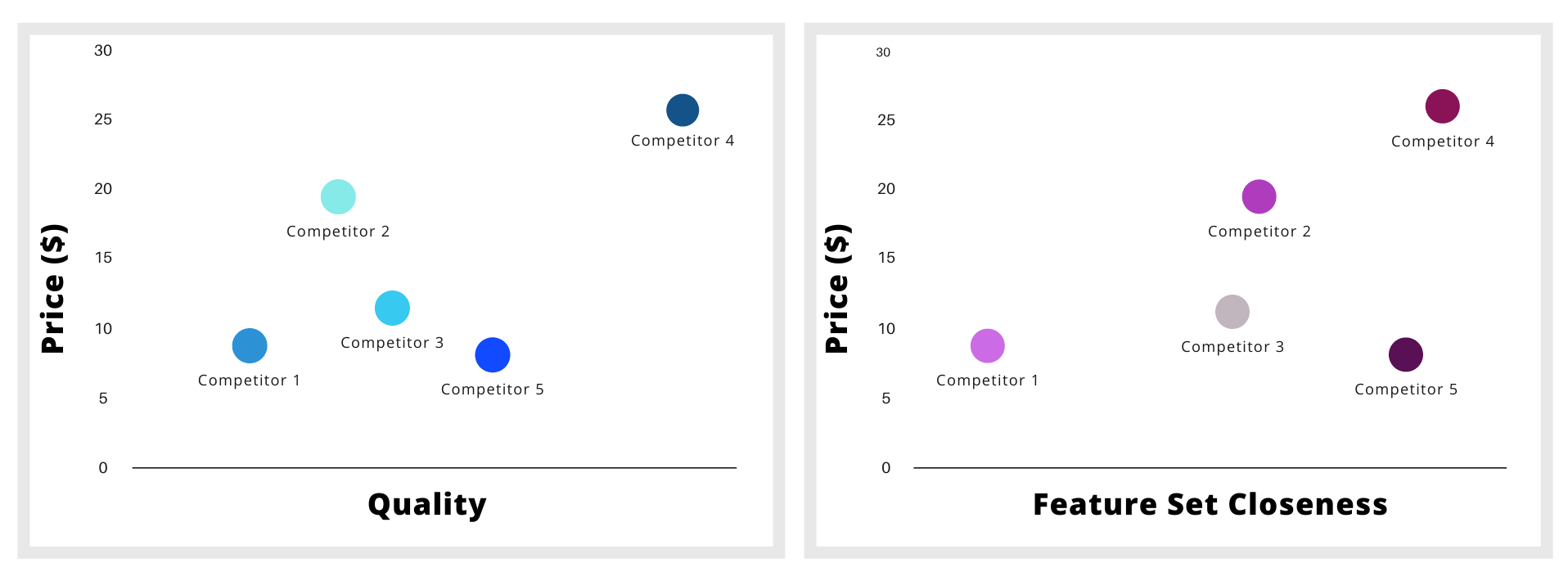

- Optionally, you could use a design tool like Figma to create a chart for the data you collect, with price along the y-axis and another comparative measure—like quality or similarity of feature sets (i.e., how similar a competitor’s feature set is to your own)—along the x-axis. Here are some examples:

- Then ==decide where you want your price to fit in.== Should it be lower than, higher than, or equal to your competitors’ prices? Are there particular competitors you should price against? Where should your price fit on your chart?

- ==Consider your value props when deciding.== If your product has exceptional quality compared to the market—and quality is something your customers are willing to pay for—then you might go higher. Or if one of your value props is affordability, you might price lower than your competitors. It all goes back to your unique value props, always.