2023-04-21

# Discerning Life Questions

#DLQ10 #religion #spirituality

# The Book of Job

- Why does God allow the Innocent to Suffer?

- The Book of Job is one of the most beautiful pieces of Hebrew poetry in all of the Bible even if it deals with such a harrowing theme.

# “Everything happens for a reason”

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DTcJmIbn5nw

- Supplementary reading:

- This reading is the preface and first two chapters of his book Where the Hell is God? In simple and down-to-earth language filled with stories, this short book brings its readers to a reflection of the mystery of suffering in the Christian tradition.

- Here is its bibliographical entry: Leonard, Richard. Where the Hell is God?: Mahwah, NJ: Paulist =Press, 2010.

# Jesus’ Context

Immersing in a Pool (Jesus is Human)

I miss swimming! (Believe it or not, yes I do swim!) I want to use this as an image to describe what I think the appropriate response to suffering is. It will then lead us to a timeless Christian theological question: Who is Jesus? From here on, we will observe the life and ministry of Jesus Christ as a way of looking at how we can deal with suffering in this world.

- Why does God allow the innocent to suffer?

- How do we respond to suffering?

- One response to suffering is resentment. But another response to suffering is immersion.

- Immersion = learning how to enter the suffering of another person

- May not provide all the solutions, but it’s a good place to begin

- An image we can use to visualize immersion is swimming. It’s really about putting your whole body under water so that it all gets wet.

- Immersion = when your whole person is involved

- Problem: For many of us, Jesus is a very familiar figure. However, our images of Jesus tend to be so distant. Is Christianity jsut all about this?

- Jesus is more than just a miracle-worker.

- Proposal: Jesus is God’s immersion in our condition.

- God doesn’t just sit by the pool of our existence and gets his feet wet. He doesn’t just wade around the pool of human condition, not fully involved.

- Christians believe that in the person of Jesus, God goes underwater, fully immersed, fully involved in the human condition.

- Jesus is fully divine, but he is also fully human

- Our images of Jesus are truthful, but they are also polished

- The human element is underemphasized/neglected

- Jesus suffered too

- The “hocus pocus” moments are not what make Jesus special. But it was His uncanny, radical ability to immerse in people’s suffering.

- Summary

- Yes, Jesus is divine. But don’t forget that He’s also as human as you and me.

- His divinity is seen in His humanity. They are not separate dimensions.

- In Jesus, we will find a God who immerses and connects with the suffering of His people.

Are Crowns Still a Thing? (The Kingdom of God)

We will talk about whether or not “kingdoms” are still relevant today and why Jesus seems to be promoting one. And what does this have to do with suffering?

- The Crown show

- Likes how it portrays the royal family in a balanced way

- To understand Jesus, we must start with what He stood for: the Reign of God

- Albert Nolan’s Jesus Before Christianity (Chapters: The Poor and the Oppressed; Healing; Forgiveness)

- Reason for title: Nolan wanted to deal with Jesus in his historical context

- In Jewish society, there were these social classes:

- Phraisees: scholars and teachers of the Law

- Sadducees: priestly class; Temple authorities

- Essenes: pious group of Jews who withdrew from the city

- Zealots: revolutionaries

- Skilled workers: those who had a decent, middle-class livelihood

- Jesus belonged to this group

- ^ These groups are the minority population

- Anawhim: the poor and oppressed

- Collective term

- Majority population

- They didn’t matter; they were set aside because of their “uselessness”

- Jesus’ mission was especially for the marginalized in Jewish society.

- Who exactly are the poor and oppressed?

- Sick persons (lepers, crippled, blind, deaf, mute, etc.)

- Persons of ill repute (tax collectors and prostitutes)

- ^ Assumption: “They must have done something for God to punish them in that way”

- The Book of Job destroys the “scoreboard model” of morality.

- What was currently going on? Humanity’s flawed ways were in charge.

- The Great Prohibition: Do not consume for yourself all the forces and powers in the world!

- From Genesis; The Fruit of Good and Evil

- Implication: when humanity takes control, things tend to be corrupt

- Splagchnizomai (Greek term): “compassion” that arises from the pain of seeing something wrong

- Jesus’ response

- The English word “compassion” is not enough to encapsulate what it truly means; it’s truly painful, like a pain in the gut

- Similar to the compulsion of wanting to squeeze a baby’s cheeks

- When you see something bad, you feel compelled to do something about it

- The Reign of God is more about service than it is about power.

- Shalom: an order that yields well-being, goodness, love, peace – the things that make us fully alive. These are what God stands for

- Versus humanity that tends to be pusillanimous ( see Cards/Pusillanimity)

- It’s not about taking control, but learning how to use what you have in the service of others

- Jesus will aim to reverse

hubriswith diakonia: service to the poor and oppressed- Not a self-oriented power, but a self-bearing service

- You will find that Jesus will dedicate His life to reversing this mistaken sense of temporal retribution.

# Jesus Before Christianity

- After dealing with who Jesus is, we now focus on His life and mission by asking this next theological question: How did He respond to the suffering of His time?

- Answering this question will hopefully lead us to reflect on this other question which is closer to our experience: Looking at what Jesus did, what do we do with the suffering of our own time?

- Generations of Ateneans have read this text that you’re about to encounter. A lot of them have said that this reading has radically changed how they understand who Jesus is and what He stood for. So trust me when I say that you’re in for a treat!

- Brief Introduction of the Reading: We seem to forget that Jesus came from a particular historical context. He is a Jewish man from first-century Palestine who dealt with the problems of His day. He was not a white man who dealt with European problems as He is often depicted. That is why Albert Nolan wants us to go back to the Jesus “before Christianity”. He wants us to pay attention to the unique ways that Jesus responded to the problems of His time so that we can see how we ourselves can respond to those problems which still pervade today.

# Suffering - From “A Sacred Voice is Calling”

- To supplement your lessons for this module, let me show one of the most beautiful reflections on suffering I’ve ever read. I still get chills reading it.

- Brief Introduction of the Reading

- In this chapter taken from A Sacred Voice is Calling, Neafsey talks about our capacity to be wounded healer’s (which is actually a concept coming from Henri Nouwen) and how suffering also has a redemptive character as seen in the passion and death of Jesus.

# Ministry to a Hopeless Man

- For our last course reading, we will return to Fr. Henri Nouwen. This is the third chapter of his book The Wounded Healer (which is one of my personal favorites) . In this chapter called “Ministry to a Hopeless Man”, Nouwen talks about the need of entering the suffering of someone at the brink of death. The call to Christian leadership is one that is unafraid of suffering, willing to wait in both and life, and always eager to be in solidarity.

- Enjoy! And may you be inspired to heal after reading this text.

# Supplementary Lecture

- As a supplementary resource for this module, listen to this short talk about hope given by Fr. Michael Himes. He talks about how we can proceed with life hopefully even when things do not go our way. I invite you to watch the whole video, but the meat of the matter for our purposes begins at the 10-minute mark.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JF2gBVo7wdE

# Biology of Science Fiction

#BIO21i #biology #sciencefiction

# ECOLOGY AND WORLDBUILDING

# Ecology: Actual and Speculative World-Building

- Ecology is the study of the ==interrelationships== between organisms and their environment.

- So as you can imagine, any sci-fi work that endeavors to have some biological elements in its work should find basic ecological knowledge essential.

- Also, it brings us back to the Red Queen Hypothesis, which says that populations have to keep evolving to survive alongside a changing environment. Full circle.

- Here’s the

lecture I gave during a synch session for last semester’s class.

- Four levels of ecology:

- Individual ecology: you looking at an individual organism and how it interacts with the environment

- E.G. individual’s tolerance of changes in physical/chemical factors like sunlight, ph temperature, salinity, and nutrient levels

- the individual ecology is very much tied with the species Cards/Niche

- individual level ecology is also often called behavioral ecology because how an individual behavesin response to its environment is an important part of individual ecology

- Population ecology

- evolution happens at the population level

- demographics (e.g. life expectancy, mortality rates, birth rates)

- inter-species relationships (e.g. predation, parasitism, mutualism)

- Community ecology

- Population is a group of same species living together; a community is a group of different species…an assemblage of different species living together

- E.G. coral reef

- Ecosystems ecology

- E.G. climate, nitrogen cycle…

- Individual ecology: you looking at an individual organism and how it interacts with the environment

- Four levels of ecology:

- And here’s an

extension, which highlights community succession in relation to terraforming and using Dune as an example. Sandworms also make an appearance!

- Pioneer organisms/species: the first to settleon a barren landscape and they are the ones that will prepare that environment for future organisms

- Typically very simple organisms like bacteria

- Climax stage of a community is where there are fe wdominant species (usually trees) and this is the state that the community will stay in for a very very long period of timeuntil a major disturbance disrupts the community and usually sets it back to zero

- A disturbance is any discrete event that will kill off individuals in a community and will usually reset the community back to zero (e.g. floods, forest fires)

- Terraforming: converting a non-living landscape into a living landscape – a landscape that can sustain life

- Core idea: community succession

- Pioneer organisms/species: the first to settleon a barren landscape and they are the ones that will prepare that environment for future organisms

- Like I say at the end of the video, there’s so much more to say about ecology. There’s also climate and biodiversity; those are also ecological because they speak of the environment having an impact on living organisms and vice versa (the global temperature ain’t just warming itself, no sir). Something ecological explains:

- why humans, Cardassians, Klingons, and Romulans look different despite coming from the same [albeit very, very distant] ancestor;

- why kaiju are so damn huge;

- the whole plot of Nausicaä, which we could have just as easily used as a reference for this Module as well;

- how Eloi and Morlocks diverged from H. sapiens;

- why the Tlic’s natural hosts gradually evolved to resist their parasitoid behavior, forcing them to use humans instead;

- how MEV-1 transferred from bats and pigs to Gwyneth Paltrow;

- what the idea of GMOs spreading into the wild and mingling with natural organisms kinda scary;

- why the heptapods and the sandkings and the Moclans and all the other aliens we’ve encountered look and act the way they do; and

- why the worlds of Dune or Alimuom or even Nausicaä may end up being our futures if we aren’t more careful.

- In case you haven’t noticed, that’s virtually all of the readings that we had this quarter!

- Just a brief note on that last one: out of all the natural biomes on Earth, only one is expanding, and that is the desert. Human activities, particularly water extraction and habitat destruction, are destroying many ecosystems’ capability to support life and turning them into wastelands. It’s ecological disturbance on an unprecedented global scale. Will nature be able to bounce back and start fresh the way communities in succession do on a smaller scale?

Points for Discussion

- Explain in your own words the relationship between ecology and evolution.

- For each of the four levels of ecology, give an illustrative example from one of our texts in this course.

- What for you is the most critical ecological problem that the Earth is facing now? Why? Is there any way that science fiction can help us approach that problem?

# Political Ecology

- The principle that underlies ecology is the same idea that makes fictional worldbuilding work: ==the systems that comprise the world are complex, multilayered, and intersect with each other in a variety of ways.== Often these intersections are experienced at the level of the individual–the climate and water cycle, for example, combine to give you the rainy day, while the rotation of the Earth and the clouds and the smog we release into the atmosphere give us what we know as a sunset.

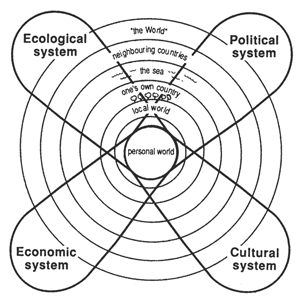

- When we use ecological principles to read worldbuilding, it might be helpful to apply this same idea of interconnectedness. In the real world, one framework that works this way is the idea of Political ecology: a framework that views ==society as an ecosystem==, with its parts relating to each other the way ecological factors do.

- The interconnectedness of our categorizations–our multiple identities as shaped by society as well as the social systems in which we are enmeshed, described by the framework known as intersectionality–is not by any means a novel idea: we are very much ==products of the many overlapping systems== that make up the world in which we live, such as race, class, gender, disability, sexuality, and so on.

- What political ecology does is look outward from that nexus of experience, and propose that ==our intersectional experience may be a reflection of the world as a whole, and that these different systems all intersect with and influence each other in the manner of an ecosystem.==

- Ecology, politics, economy, and culture–as well as the abovementioned systems within them–interact on multiple levels, ranging from individual peoples’ experiences to the way the world works.

- Take politics and ecology. At the macro scale, our political decisions influence–and are influenced by–the environment in which we live: policies on carbon emissions and global warming, for example.

- But at the level of individual countries, the Philippines, by virtue of where it is located, bears the brunt of worsening tropical storms and typhoons, forcing our government to make political decisions about disaster mitigation and response, even if we far less carbon and contributing far less to global warming than countries like the US and China. (This is not to say we shouldn’t do our parts, of course, but we can only do so much, you know?)

- And at the level of individual people’s experience, these decisions affect our class suspensions, our jobs and livelihoods, the safety of the places we live, the food we eat–the whole shebang.

- And this is all just today: ==think of the wealth of natural resources possessed by the developing world, and how this attracted the attention of colonial powers with power and weapons==; the history, culture, and politics of our country and many others like it, as shaped by colonial violence, can very much be traced back, in part, to the fact that we have nice stuff and they wanted to take it.

- For another excellent look at how ecology and politics have shaped each other, check out this awesome thread from Twitter by Latif Nasser about another intersection of geography and politics: the relationship between the Cretaceous-era shoreline of North America and voting demographics in the United States, a relationship that has undoubtedly shaped US elections–and, thus, the politics of the world–for decades.

- Put another way, ==this kind of interconnectedness has been present in speculative fiction–whether foregrounded or not–for centuries.==

- In Greek myth, Gaea, the Earth Mother, and Ouranos, the Sky Father, are married, which was a clear allegory for the relationship between land and air, heaven and earth.

- In Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri, a computer game about humans trying to colonize a seemingly uninhabited alien planet, excessive ecological damage caused by human activity causes the native fungus fields to expel swarms of psychic worms that attack the human colonies (in Civilization terms, think of them as AI-controlled neutral barbarians, except they explicitly respond to environmental destruction, and also they burrow into people’s flesh and lay eggs in their brains).

- In Dune, a text for this module (seriously, start reading it if you haven’t), the spice melange is a substance found on the planet Arrakis, and with its use in everything from food to trade to clairvoyance to space travel, it represents immense potential political leverage, enough for the desert world to attract the attention of foreign colonizers who would otherwise have left it well alone. Except here, the WMDs are real, but nobody controls them and the “W” stands for “worm.”

- And in James Cameron’s Avatar, the plants and animals of the planet Pandora have the ability to physically interface and communicate with each other, implying both a common evolutionary ancestor and the whole idea of interconnectedness itself.

- From a literary perspective, that’s really what ecology and worldbuilding are all about: ==interconnectedness==, the complex overlapping relationships that connect the elements of a fictional world in much the same way as the elements of our world and the facets of our society are connected. As we read our last set of texts for this semester–“Process,” Alimuom, Dune, and “Microbiota and the Masses: A Love Story”–we invite you to consider them as examples of interconnectedness, texts which use the science fiction novum to hyperbolize and make visible the ways in which our world is held together.

# Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Post-Apocalypse

- Let’s talk about kaiju.

- There is a strand of Japanese literature that some scholars refer to as bomb literature (take a guess where that specific term comes from). The important thing to note here is that the bomb is used not just as a literal explosion or disaster, but as a ==narrative structure: a devastating event that forever divides life into a before and an after.==

- The kaiju is a fascinating science fiction archetype, in large part because, while it is a category of creature, narratively speaking it tends to behave more as ==part of the setting== than as a type of character.

- A kaiju is definitionally so large that it’s hard for regular human characters to interact with them in any way that’s meaningful for the kaiju—we live around and in response to kaiju; they’re something a person survives rather than something a person fights.

- When we call a kaiju a force of nature, that extends to their role in the narrative—in addition to often embodying nature’s wrath, or the power of something so vast as to be comparable to it (see: Godzilla as embodiment of the atom bomb), our conflicts with kaiju behave more like ==person-versus-environment conflicts== rather than person-versus-person texts.

- The human response to kaiju, therefore, can be read as a way to talk about ==the ways humans respond to large-scale crises==; it’s no coincidence, after all, that kaiju movies often resemble disaster films.

- Godzilla and King Kong are archetypal examples: the organized human response is a military one, where we respond to forces of nature with force of arms.

- The Pacific Rim franchise provides an interesting twist, where kaiju are fought using giant jaeger robots that can only be piloted by drift-compatible humans capable of understanding each other on a deep and fundamental level—love, it seems to say, is the only thing that lets us become big enough to cancel the apocalypse and fight the monsters on their own terms.

- And in Dune, which we’ll discuss later in the module, the sandworms are kaiju which our protagonist learns to ride—the impossible monster is something you learn to use (if never completely taming it), and that act is how one asserts dominance over the world.

- In some ways, the Ohm or Ohmu in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind operate very similarly to traditional kaiju–in addition to being enormous fuck-off bugs, they’re also sort of stand-ins for the person-versus-environment conflict at the heart of the film (although unlike most kaiju, the Ohmu retain the science fiction bug’s characteristic of swarming).

- The setting of the film is very much post-apocalyptic–and by “post-” we mean “a thousand years after,” but the text gives us a world with a very long memory, so who’s counting–and the Ohmu are an integral part of that apocalypse, a visceral reminder that the old world is gone and a new one has been revealed.

- And yet, the film is not a kaiju film, insofar as it also presents a hyperbolized environment distinct from (albeit connected to) the _Ohmu–_the Toxic Jungle/Sea of Corruption, a living reminder of the devastation inflicted on the Earth by humankind in the history of this movie.

- Design-wise, the Ohmu are another kind of estranged bug-based novum, but their narrative function is both similar to and far different from the typical science fiction bug. For starters, they’re not alien, and in fact ==seem deeply tied to nature and the ecosystem.== This has the strange consequence of making the Ohmu both more and less alien than typical kaiju, giving them ==closer ties to the Earth== while also emphasizing ==how the Earth itself has become estranged from humanity== in the world of the text.

- Jokes about King Kong aside, another way in which the Ohmu echo familiar kaiju tropes is the element of ==human connection, of bridging the gap between human and creature==, through the story of Nausicaä herself.

- While the Ohmu are known to Nausicaä and the rest of humanity at the outset, the film (and the manga) reflects her journey to attempt to understand and eventually form a bond with the creatures.

- It’s significant that at the beginning of the film, during her–and our–first up-close encounter with an Ohm (the dead one which she finds and whose eye she takes), we see that her attitude towards the creature has more caution and reverence than outright fear or revulsion.

- While the dead Ohm is our first encounter with the species–signifying a world with a lot of history, but also a lot of history that is unknown to us–it is certainly not Nausicaä’s first, and yet she still regards it with the kind of wonder and respect that will come to be important in (and emblematic of) her future dealings with the Ohmu.

- Without spoiling anything (a reminder that your experience of these discussions and discussion boards will be much enhanced if you read the readings first), the Ohmu end up being very interesting figures from a semiotic standpoint: at once totally unlike typical kaiju and also archetypal representations of how kaiju function in a text. They are huge, powerful, enigmatic, meaning-rich, and cool as hell, and fine examples of how to create fun, interesting creatures that make sense and add weight to a story without needing to be fully explained.

You know what else doesn’t need to be fully explained (but it would be cool)? Your possible answers to these discussion prompts! Answer any or all.

- How does the Ohmu’s design impact the plot and discourse of Nausicaä? Does it matter that they are kaiju, bugs, or kaiju bugs?

- Discuss Nausicaä’s relationship with the Ohmu and how it develops throughout the film. How does it compare to the relationship between the Ohmu and the rest of humanity?

- If you had to name the baby Ohmu (if you’ve watched the film, you know the one), what would you name it and why?

- What sorts of organisms seem to have survived the ravaging of nature in this film’s setting? From what we know of the real-life biology of their current counterparts (presumably their ancestors), why does this make sense?

Ron’s Notes:

- Speaking of apocalypses, the future shown in Nausicaä is pretty scary from a biological perspective.

- Even in our current times, many biologists believe that we are in the middle of the ==sixth mass extinction event== that the 4.6-billion-year-old planet has seen (the fifth one was the “K-Pg Extinction” event 66 million years ago, which is well-known because it wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs, among many other species of life).

- This is the general belief because the rate of extinction of species in the last 100 years has exceeded the extinction rate normally seen over thousands of years. Unlike the five mass extinction events that preceded it, this is the ==only one that’s caused primarily by the planet-altering activities of one species.== Any guesses on what that species is? Not bad for one that’s been around for only around 200,000 years!

- There are five major causes of biodiversity loss or extinction in the world: pollution, overexploitation of living resources, climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species.

- As you may imagine, these five ==don’t necessarily have to be mutually exclusive.== For example, overexploitation of forest trees for lumber is a primary cause of habitat loss, air pollution has been a cause of climate change, and wildlife trade (which is a form of exploitation) has caused the proliferation of invasive species.

- Assuming that Nausicaä shows Earth in the future (making it an example of the “Dying Earth” subgenre of dystopic sci-fi), which of the five drivers of extinction could have played a major role in shaping that future? If you think about it from that context, Nausicaä becomes a cautionary tale about how we’re living our lives at the present despite being set many, many years forward in time.

- Remember what we said about sci-fi speaking more of the present than of the future?

# Alimuom: I Need Some Space

- Keith Sicat’s Alimuom is a Filipino science fiction movie built around hyperbolizing a deceptively simple premise: ==what if the soil became too toxic for agriculture?==

- The film builds a world around answering this question, giving us high-concept takes on familiar topics—OFWs, anti-government insurgency, and my personal favorite, shitty state bureaucracy—that combine into a setting that is at once far-flung and deeply familiar.

- Our POV character as we wade through this world is Diwata Encarnacion, a young college teacher in a long-distance marriage with an OFW (outerspace Filipino worker) stationed around Jupiter, with whom she has a son she is essentially raising without the husband she can only afford to call on select occasions. But Diwata is more than a wife and mother: she is the daughter of a botanist embittered by poor treatment from the government, and she has a long-lost sister whom she misses dearly.

- It is this network of relationships that weigh on and drive Diwata through the film’s main plot—her involvement with a government effort to identify mutated seedlings that seem to exist in defiance of both the country’s toxic soil and the national ban on agriculture enacted in response to it.

- Given all this, Diwata kind of has to be an interesting protagonist to be able to hold all these disparate threads together, and she establishes herself as such within minutes of her first meeting with her would-be employer from the Department of Agriculture. She’s rightfully suspicious and perhaps even a little embittered—the society in which she lives has deeply hurt her father, kept her husband lightyears away, and given her students who seem to want for themselves the same life she resents—but that doesn’t stop her from being driven and take-charge as hell. Diwata is a ==true science fiction character==—a young Filipino professional willing and able to assert her worth, even to the government—and every time it seems like the plot might railroad her into the next story beat, she takes charge of the narrative and gets there herself.

- Diwata’s arc throughout the film, as with any good social science fiction work, gives her–and us–a taste of how society in this quasi-post-apocalyptic Philippines works; we see both how the government works and how it affects people on the ground. That society is messed up is hardly a surprise–something common to both the Filipino experience and typical dystopian fiction, whose aesthetics and sensibility the film invokes pretty blatantly–but what is a surprise is the degree to which society has failed, and in what ways. We never see every aspect of how this world works, but we do see the ==intertwining of personal life with social policy== that both makes this fictional Philippines feel real and lived-in as well as helps our minds speculate about the parts we’re not seeing. You never need to present the whole world; you just need to show a cross-section that feels real enough for the audience to help you fill in the gaps on their own.

- Part of what makes Alimuom such an intriguing film is that, apart from the through-line of Diwata herself, some notable scenes seem at first glance to not connect to the overarching plot. Diwata’s long-distance marriage never links up with her government job, plot-wise, and there’s an odd scene in the middle of the movie involving Diwata, her close friend who only exists in this one scene and nowhere else in the film, and a spider-themed dancer whose performance needs to be seen to be believed. While the film does give us a cohesive central plot that does resolve itself by the end, the question of what the film is actually about requires us to consider everything it presents us, even the subplots and scenes that don’t seem to relate to the main plot in a literal way.

- And yet, perhaps such a structure really is the most honest way to tackle the subjects that Alimuom is trying to tackle–both as a science fiction film and as a Filipino science fiction film.

- A film about terraforming is necessarily a film about ecology, and the logic of ecology–myriad systems and elements all interconnected and interdependent–is ==not a logic that can be captured in a straightforward narrative arc.== (It’s why the Avatar movies are the way they are.)

- And this reflects the Filipino experience too: our lives, like Diwata’s, exist at the nexus points of dozens of relationships and histories, both personal and national, and sometimes the story that needs to be told is the story about ==attempting to acknowledge and navigate that complexity. ==Perhaps that’s what it really means to survive in the future, this film suggests, and maybe that’s all terraforming ultimately is: ==a reckoning with complexity, and an attempt to make it work for good.==

- What aspects of Philippine society do you see reflected in Alimuom? How have they been hyperbolized, and why do you think they have been hyperbolized in this way?

- What do you make of how the film ends? Why do you think Diwata makes the choices she makes, and do you agree with them? Why or why not?

- Alimuom is really, really horny. What’s up with that?

# Planet-Size X-Men: Here Comes Tomorrow

- Planet-Size X-Men #1 is not an especially complicated story–it has grand proportions and enormous stakes, yes, but the sequence of events is quite simple.

- On the face of it, it’s a story about a powerful group of superhumans trying to terraform Mars, turning it into a living world and a home for their warlike, isolationist brethren.

- On another level, it’s a story about politics and problem-solving, creativity in the face of seemingly impossible problems of geography, territory, and nation.

- And on still another level, it’s a story about ==unity and collaboration==–a theme in the current X-Men run, as you may have noticed while reading HOXPOX–and about ==what marginalized people can accomplish if they work together.==

- The comic opens strangely: with the image of asteroids in space, the expanse of the Milky Way beautifully framed behind them, and a pair of questions being asked. We do not see the asker or their audience, so while they are being spoken in the world of the text, it initially seems as though the questions are directed towards us, a provocative inquiry in the face of the seemingly lifeless void.

- These questions are what Planet-Size X-Men #1 is about, both in a literal sense–the logistics of superpowered terraforming–and in a thematic sense: ==what kind of work does it take, metaphorically speaking, for ideas to become real?== Terraforming Mars has been one of the big dreams of science fiction for decades now, and for a work of contemporary science fiction to so boldly take it on–and using characters who typically inhabit stories about oppression and hate and fear–is ambitious in more ways than one.

- It also has to be said, before we go much further, that this issue probably isn’t a story that you can read according to the rules of traditional Western fiction. By those conventions, it’s nothing special–there’s no real conflict, merely a problem to be solved, and the completion of the solution goes off entirely without a hitch. I would suggest, then, that perhaps this story is best read as a ==piece concerned with tone and ideas==: in telling us a story, it attempts to present grandiose science fiction concepts as well as evoke a sense of wonder and awe.

- What escalates as the narrative goes on is not tension or danger, but scope; the narrative progression of the story gives us the unfolding of the big plan, almost like a heist movie, as well as the text’s bombastic, comic-book hyperbolization of the scientific concepts necessary to make the plan happen.

- This is, in many ways, ==the science fiction version of a creation story== (which feels especially fitting considering the boast of Magneto, himself one of the Omega-level mutants involved in the terraforming project and seemingly its chief proponent, at the end of House of X #1).

- Was this line a sign of hubris on Magneto’s part? Absolutely. (This is part of why I love Magneto.) But in many ways, Planet-Size X-Men #1 sits in conversation with this line, narratively paying off Magneto’s hubris by showing that, on some level, given the power that he and the other Omegas wield–in particular, the power to create life and shape worlds, which we have always historically viewed as the realm of the divine–the hubris is at least somewhat justified.

- On the subject of superhuman abilities, one small line of dialogue in Planet-Size X-Men #1 fascinates me. I haven’t talked much about the Arakki yet–suffice it to say they’re a proud, ancient, mutant culture that has only recently been reintroduced to the wider world after going through thousands of years of suffering–but they serve both a narrative purpose and a thematic purpose in Planet-Size, continuing the theme of this being a story about ideas. For starters, it’s important that the Arakki, whose future is being decided by this comic, have a part to play in making their future happen, because otherwise the Krakoans end up looking very white-savior-ish. But beyond that, when Isca the Unbeaten, whose power is literally to never lose, introduces the Arakki mutants who will be helping the terraforming effort, the way she speaks of their powers vis-a-vis how Magneto speaks of them is certainly food for thought, and speaks volumes about how these cultures view themselves (and, likewise, about the depth of the pain embedded in Arakki culture).

- Planet-Size isn’t particularly interested in vindicating either view, but it does invite us to think about the implications of the words we use. ==When we survive trauma and oppression, do we view our abilities as gifts, or as weapons?== And in a setting where mutant powers are metaphorical stand-ins for the conditions of marginalization, in a story where those same powers are used to turn a dead world in a living one, is reality then being shaped by gifts, or by weapons?

- Planet-Size X-Men #1 is a story about how the geography and ecology of Mars–now Planet Arakko–are ==remade by people whose trauma and oppression are inextricably linked to the abilities they use to reshape a planet.==

- There is something incredibly political there–==how marginalized people use the things that cause them to be marginalized to reshape their world and create spaces for people like themselves==–but also something deeply, profoundly hopeful.

- Politics and terraforming have a lot in common, in that they are ultimately rooted in ==imagining a better world and making it happen==; they’re about possibility, and about the work that goes into making it real.

- And Planet-Size X-Men #1, a relatively simple story with big stakes and bigger ideas, reminds us that everyone has that spark of possibility in them, that the things that mark us as Other can also be what allow us to change the world, and that sometimes, the only way to find out is to roll up our sleeves and try.

Discussion Points

- Did you have a favorite part of this story?

- Talk about the Arakki vis-a-vis the Krakoans. What differences and similarities did you notice with regard to their culture, their powers, or their appearances? Did you think these were significant from a thematic perspective?

- How did reading this comic make you feel?

# Dune: May His Passing Cleanse The World

- Dune by Frank Herbert is one of the classic science fiction stories that you absolutely have to talk about when you speak of ==science fiction, ecology, and politics.==

- As previously mentioned, it’s the story of Paul Atreides, the scion of House Atreides, as he and his family come to the desert planet of Arrakis and fall afoul of the villainous House Harkonnen. Paul must contend with the various forces on Arrakis–from the local Fremen to the mysterious Bene Gesserit order to the massive sandworms that roam the sands–to come into his power, defeat the bad guys, and make Arrakis a better place.

- But before we talk about Paul Atreides, we have to talk about the ==spice melange.==

- The spice is an extremely potent substance produced by the sandworms which is highly prized within the Empire to which House Atreides and House Harkonnen belong, having uses ranging from narcotics to trade to granting psionic powers to powering spaceflight.

- The spice is seen as the main reason the Empire has an interest in Arrakis, and it is part of why House Harkonnen betrays and attacks House Atreides when the latter arrive–Harkonnen’s desire to keep the spice under their domain is what leaves Paul fatherless, sends him into the desert, and touches off the inciting conflict of the book.

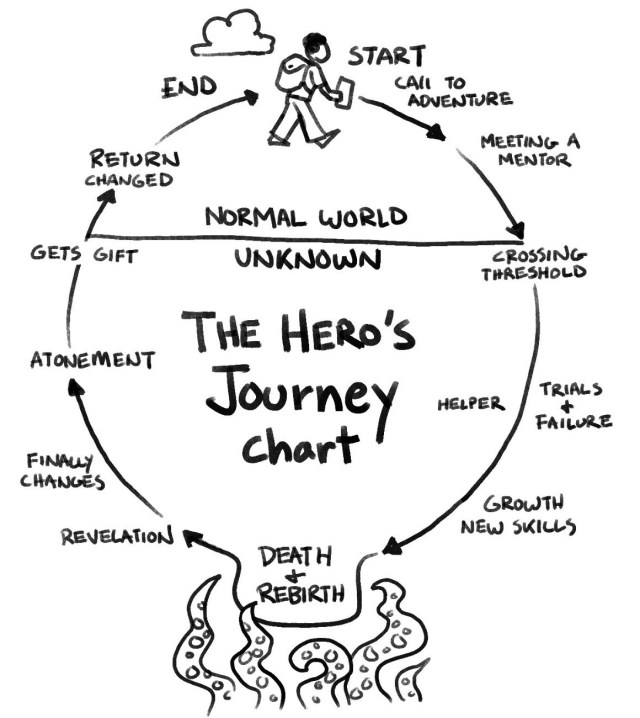

- Paul is a ==messiah figure== in every sense of the word: he is someone cast out of society and into the (literal) desert and chosen by a disempowered people, the Fremen, as their leader and savior.

- His narrative is an archetypal hero’s journey, described by Joseph Campbell as the monomyth–==the story of someone inherently noble who is laid low, rises to prominence from a position of weakness while growing in character, confronting evil, saving his people, and establishing a new status quo.== It’s a pattern we see in myths the world over, and it’s a powerful story that resonates with many of us, partly because it’s so familiar. We see stories like this and we think, good person; we think, hero.

- But one thing we have to remember is that a messiah is not just a hero in the abstract sense; ==a messiah is a hero with context. ==

- A messiah is a savior of a people, which implies that there is something from which these people need to be saved; both the marginalized and the one they choose to save them are products of the world that causes their suffering to begin with. Arrakis is a harsh desert world with little water and less compassion–to the Empire of which Paul is a part (admittedly a relatively nicer part), the one thing that matters here is the spice melange and what it represents.

- This is, in every sense of the word, a ==colonized world==–one seen mainly as a resource depot, and one whose image as a resource depot has caused it to be subjected to colonial power. And the sandworm is the ultimate expression of this: a vast and wondrous creature viewed purely as a threat and a resource generator, even if there is so much more of it literally beneath the surface.

- Paul’s taming of the sandworm, then, is the one act that symbolizes what his role as a messiah is (and, indeed, the role of all messiah figures): ==the ability to reckon with the forces of his world and break or bend them to liberate their “chosen people”== (i.e. the people who choose them).

- He bears the name of Atreides, the power of the Bene Gesserit and the Kwisatz Haderach, the loyalty of the Fremen, and the ability to tame the embodiment of the world itself, and he ends the book defeating House Harkonnen, the archetypal enemy–not with words or compassion, but with violence and a Fremen jihad.

- ==A messiah is necessarily a product of their time, place, context, and believers,== and Arrakis has ensured that for Paul, all the things that shape him are harsh, brutal, and unforgiving.

- Another thing the text highlights about messiah stories is their nature as stories: that is, as ==things that are constructed.==

- This is encapsulated in the Bene Gesserit, who for all their mysticism and special powers are also explicitly described to wield great political influence.

- The Kwisatz Haderach is not merely a messiah whom they believe will arrive; they also have a dedicated breeding program aimed at causing them to be born.

- The Lady Jessica, in her role as wife to Duke Leto Atreides and mother to Paul, is being a good spouse and mother, but she is also fulfilling a role, playing her own part in the cultivation of a narrative that takes on the shape of something sacred while ultimately being engineered by human minds for human ends.

- The thing we need to remember is this: a messiah story is not necessarily the story of a good person, but the story of a hero, a protagonist.

- As we’ve seen by now, protagonists don’t have to be good people; they’re just the people about whom the story is written.

- And the story of a messiah is often the story of a marginalized, downtrodden, suffering people in need of a hero to represent, lead, and save them.

- The Fremen choose Paul Atreides, just as the novel Dune focuses on Paul Atreides, but we have to remember that Paul–and by extension all of House Atreides–is a colonizer too. They’re nice people and they certainly do good things–one might even call them good people–but they, too, come to Arrakis as participants in the system of exploitation that mines it for spice for the Empire while largely ignoring the Fremen.

- Whether Paul can truly “go native” is up for debate (and we have to remember he’s still a young man), but by the time we see the adulation directed his way by the end of the book, having vanquished the archetypal “bad guys,” the tone of the text should make it clear: this is not an uncomplicated happy ending.

- A messiah narrative comes from a people who view themselves as oppressed, and consequently such a story reflects a desire to be saved from an impossible world. Arrakis is an archetypal example of such an impossible world, and so Dune is the story of Paul as he becomes the Dune Messiah: he represents and can master all the powers of the world–economic, political, martial, mystical, natural–and he begins his messiah journey through violence and the desert, which is perfectly in line with what Arrakis has become, a harsh, barren world torn apart by power and those who hoard it.

- And a messiah who is part of that same ecosystem–and not even truly of the people he purports to lead and save–may not be able to see it for what it is, what it looks like from below and within, and so may simply reproduce it in his attempt to end it.

- ==Oppression is just as much of a cycle as water and air,== and if Dune is about anything–other than sick-ass giant worms–this is probably what it wants to talk about: ==the damage wrought by the great beast of empire as it tunnels through the world, ruining and remaking it and those who live there in its wake.==

Discussion Points

- Pick a faction involved in Dune and talk about them. What is their stake in Arrakis? What do the planet and the spice mean to them? How do they behave in relation to each other?

- Discuss the desert as a sign. What meanings does the desert signify, in Dune and in other texts as well? What then do we associate with water (and its absence), and with the spice?

- What does the sandworm signify?

- Discuss how the evolutionary arms race plays out on Arrakis.

# “Microbiota and the Masses”: Remediation

- We’ve come to the end of our course, and we thought we’d come full circle and send you guys off in style–with a story that’s a little bit about first encounters, a little bit about quarantine, and a little bit about bioremediation. Let’s talk about S.B. Divya’s “Microbiota and the Masses: A Love Story.”

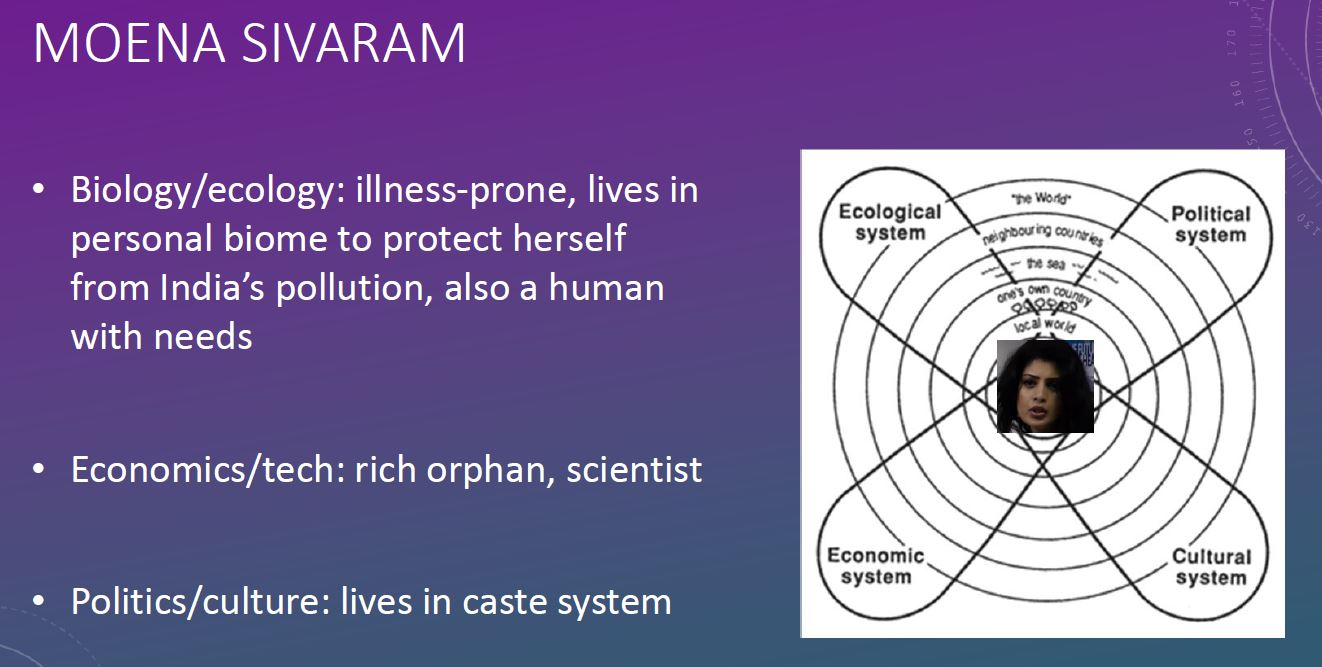

- Divya’s story follows protagonist Moena Sivaram, a famously orphaned heiress and brilliant scientist who meets and falls in love with Rahul Madhavan, an engineer who comes to Moena’s home to repair her broken SmartWindow. Moena is a bubble girl in every sense of the word, her social isolation from growing up rich in India’s caste-driven society being mirrored and hyperbolized in the text by the physical isolation of her living conditions. While Moena used to live a relatively normal (if privileged) life, the deaths of her parents in the accident that made her a household name and the onset of the risk of chronic illness triggered a huge change in Moena’s status quo: she now lives in a smart house, a tightly controlled artificial biome, in order to preserve her own health and safety. Consequently, Moena begins the story as a shut-in, being almost obsessively fastidious about avoiding infection from outside elements, never stepping outside her home, and wearing an isolation suit whenever she’s around other people. (Yeah, yeah, we know it’s unrealistic–it’s science fiction, after all.)

- But Rahul opens a crack in Moena’s walls, both literally, as a visitor to her home, and figuratively–he’s the first person Moena has seen face-to-face in months, even if he hasn’t seen her actual face thanks to her isolation suit, and this awakens in Moena a desire for more. (Plus, Rahul is hot and she’s thirsty as hell.) And so, in true romantic fashion, Moena fashions a new identity for herself as “Meena,” wanting to get closer to Rahul without the burden of her name attached, and she starts stepping outside to work with him on a volunteer effort to rehabilitate the massively polluted Agara Lake. As the story unfolds, the narrative of the lake bioremediation project is interwoven with the development of Moena’s and Rahul’s relationship, and the nature of the contamination ties it to Moena’s health as well.

- Ron’s Note:

- Just a quick note on bioremediation. This is a branch of biotechnology that involves ==using organisms or products derived from them (e.g. enzymes, unique compounds, etc.) to rehabilitate ecosystems that have been damaged by human activities==, usually (but not limited to) pollution.

- Bacteria are usually the agents used, although fungi are also known bioremediators.

- Most bioremediation has been done to clean up oil spills or contaminated groundwater but may also be used to remove toxins and other contaminants from both terrestrial and aquatic environments.

- It works on the principle of certain organisms being able to utilize these harmful compounds, breaking them down into relatively harmless compounds that they can use for their metabolism, or at least accumulating them in their body tissues.

- As you probably know, plastic-degrading bacteria are being studied for their potential for cleaning plastic pollution in bodies of water.

- And as you can imagine, genetically engineering microbes to become capable agents of bioremediation is a legitimate biotechnological application, and, by virtue of seeking to reverse the worst ecological effects of human activities, certainly one of the most hopeful and beneficent.

- Moena is an excellent example of a character deeply rooted in her setting and her environment–a political-ecology-inflected reading of her would look at all the ways in which the greater systems that shape her context are at work within her immediate surroundings and her setting.

- Isolation is a big theme for her: she is othered from her environment, her country, and other people multiple times over, her privilege and health represented by the walls of her home and her suit, and so Moena’s desire for Rahul is also a desire to break through those barriers, something she first attempts by trying to become someone else.

- And because the health of Moena’s home is so directly tied to that of her body, and her relationship with Rahul is in turn directly tied to their work with Lake Agara, we see Moena’s health and personal biome change and progress as she gets more and more entangled with Rahul as the story progresses.

- The story is very much a romantic one–I hesitate to call it “rom-com-like,” but it certainly displays many classic romcom tropes: the meet-cute, the overblown conceit of the false identity, the heartbreak when the ruse is discovered, the big romantic gesture and reconciliation at the end. But the love story is also subversive in many ways: it centers and normalizes female romantic agency and sexual desire, allows Moena to be an upper-class female romantic lead and active pursuer of a middle-class guy (in India!), and exists in conversation with multiple other narrative threads that actually matter to the text rather than simply being excuses to progress the love story.

- But at the end of the day, this is a love story (the title even says so). ==Love is necessarily an encounter with other-ness, the choice to allow that other-ness to change you, even at the risk of contamination or harm.==

- When Moena says “I’ve been infected by a man,” she is referring to multiple things at once: her sexual desire for Rahul that will later blossom into love, him opening her up to the idea of using her research to help her polluted country, the very literal infection she risks from pursuing these things, and the thought that perhaps that danger might be worth it.

- Rahul and Lake Agada mirror each other in their roles in Moena’s life: they are the things from which she is isolated lest they infect her, and yet which offer her in that very risk the opportunity for growth and change.

- Because ultimately, ==both bioremediation and love are acts of hope.==

- They require that we come to terms with the past–the traumas and contaminants that make life unliveable–and open ourselves up to imagining a different future. In introducing foreign organisms into a lifeless environment, Moena reckons with Lake Agada’s pollution in a similar way to how she reckons with herself, her heart which she describes as parched for company.

- Love and bioremediation are rooted in hope, and I think if we want to leave you guys with anything at the end of this semester, it’s hope. It’s the idea that the other can be as beautiful and life-giving as it is scary, the belief that even the most polluted lake and the deepest wounds and the most insurmountable barriers can be remade, and the faith that, while evolution is chaotic and undirected and often utterly terrifying, perhaps we really can adapt to anything.

- Ron’s Note:

- “Because ultimately, both bioremediation and love are acts of hope.” Couldn’t have said it better myself. In ecology, “hope” can be seen in the characteristic of a community (multiple species living together, like a coral reef) called resilience, which is the ==ability of the community to bounce back from a disturbance.==

- Bioremediation is a biotechnological way of supplementing a community’s natural resilience…just as love helps make us more resilient individuals.

- I’d argue that terraforming is also an act of hope, making hope a central theme of this Module :)

Discussion Points

- Talk about one facet of Moena’s identity and how it relates to her personal biome, health, and research.

- Talk about Rahul and how he acts as a foil to Moena and to Lake Agada itself.

- Do you agree (with Ron) that terraforming is also an act of hope? Why or why not?

# Creature Spotlight: Sentient Ecosystems

- The 1950 short story “Process” by A. E. van Vogt is one of a long line of works that, seemingly, progresses largely independent of anything we would normally refer to as characters.

- We’re often taught that fiction is about plot and character, that the former is ultimately about us following the journey of the latter, but some works of fiction seem to deliberately subvert that formulation.

- One of the most famous ones is “There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury, a science fiction short story about a “smart house” that runs on a programmed daily schedule and automated robotic routines, and continues to do so even in the seeming absence of the house’s occupants.

- “Process” puts a biological spin on a similar conceit, focusing on what seems to be a sapient forest with a hive mind consciousness as it responds to the arrival of a ship from beyond the world it knows.

- “Process” invites us to reconsider our idea of what a character is. While the arriving ship is piloted, we never get into the headspace of these ship-using beings, never once experience the story from their point of view. We know they have goals–the extraction of resources, first and foremost, followed by survival when the forest fights against them–but these are never treated as the main driving force of the text. And conversely, the forest in which they arrive–something that we would normally refer to as the setting of this story–is given not only the central point of view in the text, but a sense of will, agency, desire, and response to conflict, all traits we would usually associate with the more “humanoid” creatures in a text. ==It is the forest’s goals, rather than those of the ship-users, that drive this story forward.==

- The trope of the sentient location is not a new one in science fiction.

- We see it in works ranging from Marvel and DC’s Ego the Living Planet and Mogo the Green Lantern planet to the Lovecraftian Shimmer-influenced woods of Annihilation (a really good movie based on a really good book, excellent enough that I, Sir AJ, noted scaredy-cat, am recommending it despite it having some intense body horror, something I usually can’t stand).

- And while it’s easy to oversimplify this idea, either through treating the intelligent location as nothing more than an incredibly large but otherwise normal character or through reducing it to a simplistic example of how the world is alive, I think works like “Process” are a good opportunity to go beyond this level of reading and really dig into how we conceive of the notion of character–and, for that matter, how we conceive of people.

- The obvious: we assume a character is a single living entity with a single body, but a sentient location such as the forest in “Process,” with its many trees and creepers, consists of multiple bodies, and yet it still refers to itself using singular pronouns, as a single being.

- The text asserts that ==a shared consciousness that exists among multiple bodies can, in fact, be considered a single character==–and, indeed, why should our single-bodied mode of existence be the only mode we consider “normal?”

- Furthermore, as we are reminded by the prophet Osmosis Jones, ==the human body itself consists of many living organisms, including but not limited to the decidedly non-human bacteria that live in our gut, and yet we consider ourselves singular beings too–we, too, are legion.==

- Another device this story calls into question is ==point of view==–specifically, the choice of whose point of view to center.

- In a story with beings in a starship and a sentient forest, our expectation is that the main characters are the people in the ship, largely because this is the experience closer to how we imagine our own experience to be. We are used to our experience being repeated back to us by the texts we consume–I think the kids call this “relatability.”

- But “Process” deliberately defamiliarizes the more “human-like” perspective; we only ever see the beings in the ship through the eyes of the forest, and meanwhile the experience that is foregrounded is the one more alien to us, more unfamiliar. The text reminds us of ==our own tendency to foreground the more familiar perspective==, reducing the voice of the other to “setting” when we cannot see enough of ourselves in it, never mind that our definition of character might be more limited than we are comfortable admitting

- “Process” is a deceptively simple story told in an unconventional way: a story of adventure into the unknown, told from the perspective of the unknown.

- It’s a story about a consciousness that is at once very different from ours and quietly similar, and the ways in which that kind of consciousness responds to people more like us as they do the things that we would do in that situation.

- But ultimately–as with everything human beings write–it is very much ==a story about people, and the ways in which we believe all stories are about us, and what happens to the voices pushed to the periphery of our narratives as a result.==

Discussion Points

- What is the importance of the ship-users’ goal to the text and what it is trying to communicate? Why does it matter that this, specifically, is what they’ve come to this world to do?

- Semiotically, how does a living ecosystem differ as a narrative device from a “normal” character who has total control of nature?

- What do you think “Process” is saying about ecology, or people, or both?