2023-01-26

# Discerning Life Questions

#DLQ10 #religion #spirituality #philosophy

# The Need for Certainty

# Lecture 1: Living Our Questions

- Problem v.s. Mystery

2. 2 examples: org project v.s. mother. These show the difference between a problem and a mystery

3. Problem

1. begins with not knowing

2. can be solved from a disinterested/impersonal standpoint

4. Mystery

1. begins with knowing, leading to more knowing

2. invites a person into further understanding since the meaning of that mystery is inexhaustible

3. a mystery must include the person inquiring about it -> you need commitment/investment in taking deeper understanding

4. A mystery can be approached with 2 dispositions

1. Absolute certainty

1. We always operate with limited certainty; absolute certainty does NOT exist

1. You cannot fit the largeness/complexity of this world into your mind

2. When we live with absolute certainty, we resort to Reductionism: looking at a complex world from a simplistic perspective

1. Fundamentalism: a firm and rigid adherence to a fundamental set of beliefs and doctrines

1. Typically found in religious circles; laws are laws. E.G. “Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve”

2. Less about thinking, more about following

2. Relativism: Truth is ultimately dependent on the individual or a group. Objective truth does not exist.

1. The forwarding of so many different truths -> losing objective truths + a shared sense of reality

2. Also does not require thinking

3. Both of these mindsets reveal a proclivity towards control

1. We close ourselves to the possibility of other things

2. Wonder

1. The disposition of a learner.

2. It requires…

1. Constantly revisiting the ordinary.

1. Seeing the mundane with fresh eyes and perspectives

2. Engaging and allowing.

1. Not taking things as they are 2. Asking questions & being open 3. Humility.

1. About seeing the truth of who you are, rather than pulling yourself down 2. Knowing where I am right now 3. Comes from the word humus, which means soil 1. A seedling in soil is vulnerable, exposed to the elements, to the vermin, yet this is where it grows 2. This is one way you can discern a life question that will result in change/status quo — will you grow? 4. Commitment 1. You only get to know more about a mystery when you commit to it with wonder 2. Letting go & growth - Complementarities

- Atenean indecision?

- Thinking in absolutes.

- Traps in decision-making.

- Order and chaos.

- Partial and reasonable certitude.

# Biology of Science Fiction

#BIO21i #sciencefiction #biology

# MODULE 1: Introduction to Science Fiction

# The Science Fiction Genre

- Science fiction, as a literary genre, is defined largely by gray areas. In a nutshell, it’s a genre defined by fictional elements that are rooted in scientific principles while still being impossible according to our current understanding and/or deployment of those principles, but even this definition comes with caveats and ambiguity. Whose science are we using? What does “impossible” mean? How much can we bend scientific theory before we leave science fiction altogether and enter the realm of fantasy?

- This is not a course whose goal is to give you definitive answers to any of those questions. This is a course founded on appreciation, discussion, and critique, which means ==treating gray areas not as problems to be solved, but as territory to be explored==.

- Historically, science fiction has many ancestors, chief among them ==mythology==–the stories used by ancient civilizations to attempt to explain the workings of the universe. While we now refer to these as fantastical narratives, to ancient peoples, these were the result of earnest, rational striving using the tools they had at the time in order to ==explain phenomena for which they had no definitive answers==–in short, early forerunners of science and science fiction.

- Later on, as ==political, utopia, and enlightenment stories== emerged throughout human history, they too displayed characteristics we now associate with science fiction, centering such concepts as ==alternative visions of society== and the ==primacy of human reason== in shaping and understanding the world.

- One important thing to remember is that science fiction stories are as much about the present as they are about the future. Science fiction exists at the ==intersection of possibility and critique:== we imagine it out of our dreams of the future as much as we extrapolate it from the realities of the present. When Orwell wrote 1984, he was both speculating on how technology might enable a government to spy on and control its people as much as he was commenting on the surveillance state that already existed in the United States as he was writing. This can inflect science fiction with hope and darkness in equal parts: the bright spots we see in the present, as well as the problems, can all be amplified and hyperbolized through the lens of future society and technology.

- The perspective of science fiction, thus, is that ==we carry our present into the future.== ==Reason and human agency and causality==, not destiny or prophecy or the associative logic of magic, are the driving engines of reality; science fiction holds that ==the universe can be understood, that history makes sense, and that logic is the ordering principle of narrative== (even if it’s a logic we do not currently understand).

# Darko Suvin: “On the Poetics of the Science Fiction Genre”

- Suvin’s definition of science fiction hinges on two key descriptors.

- First, he describes science fiction as a genre that “takes off from a ==fictional (‘literary’) hypothesis ==and develops it with ==extrapolating and totalizing (‘scientific’) rigor.==”

- Science fiction asks the question what if, creates hypotheses that bear some kind of ==social, cultural, or symbolic resonance== (e.g. “what if capitalism literally forced you to buy more years of life”–see the 2011 film In Time), grounds these hypotheses in ==scientific logic== (e.g. “capitalism forcing you to buy years of life is possible if humanity is genetically engineered a certain way), and then builds its stories from these premises.

- At the heart of a great science fiction story is a ==resonant (“literary”) idea==, built up with the ==logic of currently understood science== and turned into the engine of a narrative.

- Suvin further writes that “the effect of such factual reporting of fictions is one of confronting a set normative system… with a point of view or glance implying a new set of norms.”

- Here, the “set normative system” is the ==“real world,"== the context in which the author and reader live and which the text inhabits.

- Every fantastic fact in science fiction is an implied ==critique of reality==–if you make the sky pink on your alien planet, you implicitly ask why the sky we see isn’t pink.

- When we see a kaiju like Godzilla or a fictional alien invasion like the zerg from Starcraft, we ask ourselves how we as a society actually would react to this kind of catastrophic disaster (spoilers for the year 2020: apparently not well).

- More realistically, a world of social control like that of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale asks questions like, “What if the sex-and-gender-based social systems that control our lives were somehow even worse and had more concrete physical manifestations?”

- First, he describes science fiction as a genre that “takes off from a ==fictional (‘literary’) hypothesis ==and develops it with ==extrapolating and totalizing (‘scientific’) rigor.==”

- Suvin anchors all this on what he terms the Cards/Novum, the “strange newness” at the heart of a science fiction work. The novum is the fantastic element of a text, the point of difference between a science fiction text and the reality in which the text exists.

- A work can, of course, have multiple nova, ranging from people to creatures to technology to places to physical laws and phenomena.

- The novum follows the logic of science fiction: in a good science fiction story, the novum has a “literary” resonance–it carries a kind of social, cultural, or symbolic meaning with it–but exists in the world of the story through scientific logic and rules.

- When we see Godzilla, we think of a metaphor for the atom bomb, a wild force of power and destruction, but he exists in the world of the text as a mutant creature, an accident of genetics. And the best science fiction stories ==portray the metaphorical and logical sides of the novum as in harmony with each other==: Godzilla is mutated, usually, by radiation from the atom bomb, so even in the world of the text, he is the embodied power of the weapon that he represents.

- Suvin also goes on to talk about two other principles at work in the science fiction text: Cards/Cognition and Cards/Estrangement.

- Cards/Cognition is our ==understanding== of something, the textual representation of our ability to recognize the ==meaning== in a symbol.

- Cards/Estrangement, conversely, is the ==portrayal== of something in a way that renders it ==bizarre or alien== to us (one might also call it defamiliarization).

- When we look at the novum, or indeed at any fantastic element in speculative fiction, both cognition and estrangement are at work: we can ideally recognize what the novum represents, both in terms of symbolic meaning and scientific principle, but we can also see the ways in which the work renders it fantastic, scary, wondrous, and unreal. The creative tension between cognition and estrangement is what drives science fiction–in terms of individual text, genre as a whole, and our experience of both–forward.

# Evolution as the Framework for Science Fiction

“Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” -Theodosius Dobzhansky

- ^ This will be our guiding principle throughout the whole course

- Just as evolutionary concepts inform biological studies, so do they inform the understanding of science fiction texts with biological nova.

- Episode 1 - Biology of Science Fiction: Cosmic Red Queen

- Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland: “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

- Cards/Red Queen Hypothesis: a species must adapt and evolve not just for reproductive advantage, but also for survival because competing organisms also are evolving.

- Cards/Evolutionary Arms Race: an ongoing struggle between competing sets of co-evolving genes, phenotypic and behavioral traits that develop escalating adaptations and counter-adaptations against each other, resembling an arms race

- Gunn - The Worldview of Science Fiction

- Gunn proposes a worldview of science fiction that is based on the premise that humanity is adaptable. Humans have the intellectual ability to choose a course other than that instilled by their environment.

- Four principles:

- The universe is knowable

- Humans are adaptable

- As humans encounter new stimuli, they grow and change in order to incorporate the new stimuli. Denial of change is characterized as a backward attitude in science fiction. Certainly the good old days, the period of time prior to change, can be appreciated, but science fiction, in its forward-thinking attitude, will recognize that the good old days were never really that good and that change is necessary for growth of the species.

- Humans can overcome their natural instincts and responses to stimulus

- Does not overly concern itself with characterization

- The focus in a science fiction plot will be on external events and the repercussions of those events

Points for Discussion:

- How are Suvin’s and Gunn’s ideas on the science fiction genre consistent with each other? How are they conflicting?

- Think of a science fiction text (i.e. book, movie, anime, TV show, comics, etc.) that you know. How does evolution inform its main plot and/or characters?

- In her Introduction to her novel _The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula Le Guin says that “Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.” Is this consistent with how you view science fiction? How do you relate it to Suvin’s and Gunn’s definitions of the genre?

# Semiotics and the Novum

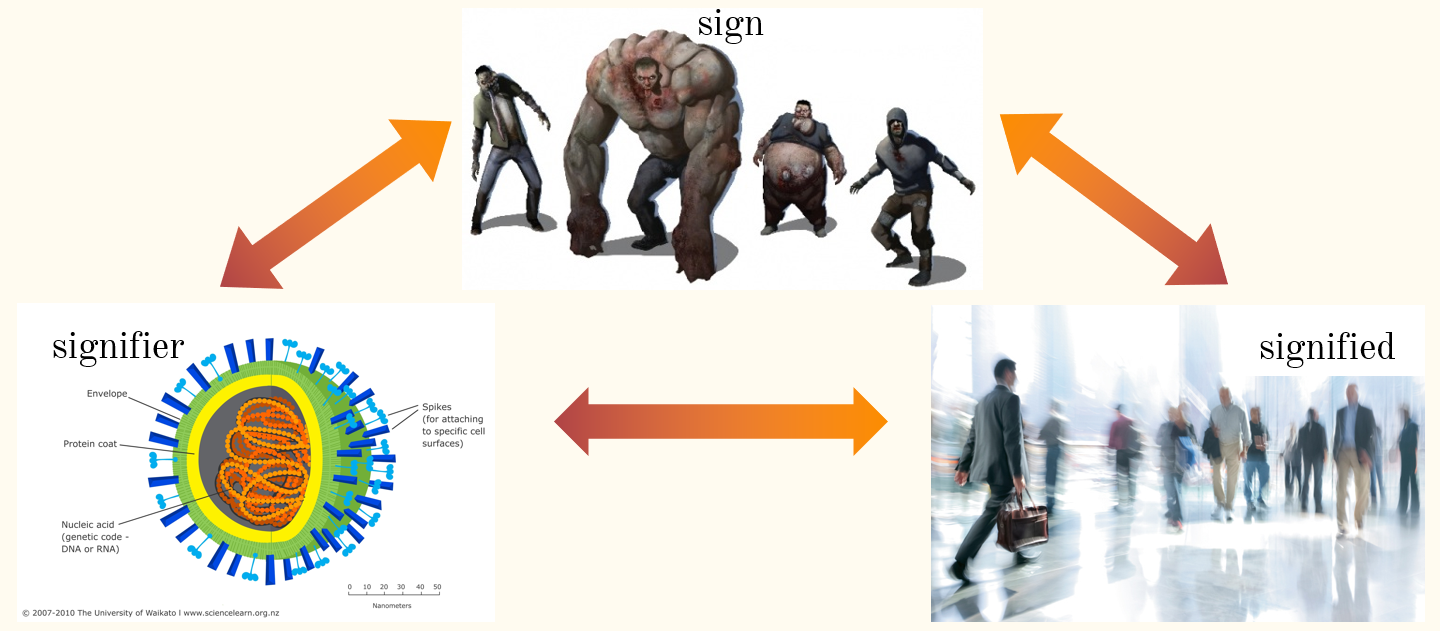

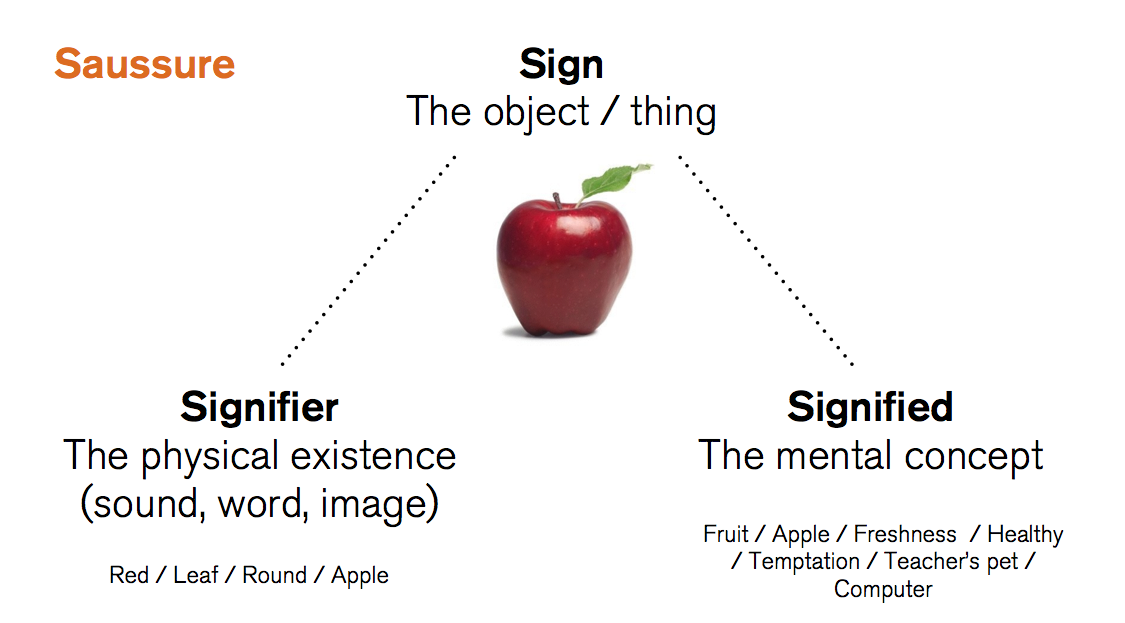

Science fiction as a genre is highly driven by signs and symbols. We can look at Ferdinand de Saussure’s definition of a sign as a system of meaning consisting of a constructed relationship between a signifier (the physical form of a sign which communicates meaning) and a signified (the abstract meaning/s being communicated).

Because these relationships are constructed and based upon ==convention==, a signifier can have many meanings, and often we have to parse them through ==context==–the color red can be seen to represent health if seen on an apple, love if combined with the shape of an abstract cartoon heart, or caution or attention if perceived in the context of the octagon of a stop sign. We can then say that a stop sign is a sign that uses the color red as a signifier to communicate caution and attention as signified meanings. (Although it must be said that by now, the image of the stop sign is so ingrained in many of us that the signified meaning is pretty much just “stop.”)

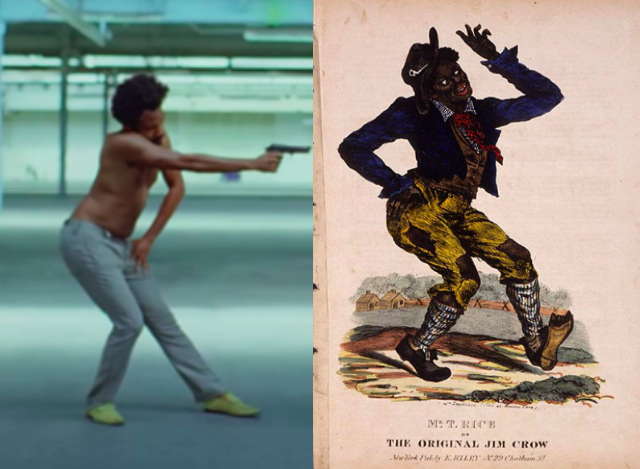

Darko Suvin’s nova can be interpreted in much the same way in terms of how they operate within science fiction texts. Through the dynamics of cognition and estrangement, a novum often ==represents a concept from reality (the signified) that is twisted into an often-literally-alien form (the signifier).== In a good science fiction work (i.e. one that integrates the novum as a core part of the text’s discourse rather than simply using it as window dressing), it’s often a good strategy to begin reading the work by trying to figure out what meaning/s the novum is attempting to communicate.

For example, the zombie, a classic monster in movies and popular culture, is often explained as the product of a virus or other infectious agent when it’s in a science fiction text. The zombie virus, then, is the novum, the science-based fictional element that makes the text a work of science fiction.

- Now, depending on the specific text, zombies are often used to represent all manner of things: zombie movies set in malls often cast their zombies as mindlessly ravenous hordes against a backdrop of consumer goods, suggesting a reading based on consumerism’s ability to drive us mad.

- Conversely, a zombie movie where the protagonists explore a post-apocalyptic wilderness or urban landscape tends to create the feeling that the zombies involved are stand-ins for humanity in survival mode, the loss of humanity that can occur in desperate situations.

- In this formulation, the sign is the novum, the zombie plague.

- The signifier, the concrete container and conveyor of meaning, is the science-based element of a pathogen.

- The signified, the abstract theme/s or ideas/s that the signifier is made to represent, is **consumerism or desperation–the fear of the other–**or whatever it is that the film in question wants its zombies to stand for.

In short, a good starting point for reading a piece of science fiction might be to begin by identifying the novum, and then trying to articulate it using a formulation like, “The novum in this text is [sign], which uses [scientific grounding] as a signifier to communicate or represent [social/cultural theme/s and/or idea/s] as a signified.”

It’s important to note that there is even less direct correspondence of meanings between signifier and signified when we speak of the science fiction novum than there is for other signs; the metaphorization present in science fiction necessarily loses some of the meaning of the signified even as it hyperbolizes and clarifies other aspects of it. The point of science fiction is ==never to completely reproduce anything==–whether it’s science or the abstract themes that it’s using science to discuss–but rather to ==make us think about and appreciate the ways in which scientific theories and our conceptions about society, culture, and philosophy can inform and comment upon each other.==

One final note: the reason I hate the word “symbolize” is because it’s so easy to overuse. Remember, ==a metaphor is when unlike things are compared to one another with the intention of making a point.== If a movie shows humans attacking aliens with missiles, you cannot say the missiles “symbolize hostility”–they’re a direct consequence of hostility. Not everything is a symbol, and indeed, not every theme in a science fiction text is a direct result of its novum or nova. Don’t be too trigger-happy with your analyses.

# Language and Biology

- One very common source of curiosity regarding non-human animals is whether or not they have or are even capable of language.

- It’s interesting to note at this juncture that one way by which human language has been distinguished from other animals’ modes of communication is that it is the ability to routinely invent new signs or words. That is not to say, of course, that other animals cannot read and understand signs.

- There are all sorts of visual, auditory, and tactile chemical cues that animals use to understand one another, like bright colors usually meaning danger!

- It’s just that ==only humans may be capable of routinely inventing new signs or new meanings to existing ones.==

- Aside from that, human language has some properties that other forms of animal communication lack. According to linguistic anthropologist Charles F. Hockett, only human language has the following features:

- displacement (communicating things that are not present)

- productivity (creating new words to add to a language, specifically to its lexicon)

- cultural transmission

- duality (consisting of individually meaningless elements that can together form larger meaningful elements, such as sounds together making up a complete word)

- prevarication (intentionally making false or meaningless statements), reflexiveness (using language to talk about language)

- learnability

- Other features such as arbitrariness and semanticity may be present in communication among other primates or to a certain extent other animals (like dolphins, which are believed to communicate through their clicks, including unique names for one another), but ==only human language has ALL of these properties.==

- That other animals have some form of communication is, of course, undeniable. Ants and many other insects use chemical signals in the form of pheromones. Birds use their sounds and a combination of anatomical traits and behavior, such as fluffing their feathers, to transmit a message. Cuttlefish change the color of their skin to show aggression. So that leads us to the next oft-asked question concerning language: is intelligence necessary for the type of language that we have? What do we even mean by intelligence and “intelligent species,” which is a term that we often see in science fiction?

- It’s not necessarily an easy question to answer. Many have linked intelligence to cognition and consciousness.

- The essence of Cards/Cognition can be captured by the ==capacity for perception, thinking, memory, learning, decision-making, problem-solving, self-control, and, perhaps most importantly, prediction.== ^cec67f

- It has been said that only humans have a concept of the future and planning for the future. However, some recent researches such as one done in Stockholm University have shown that planning and self-control behavior can be found in some animals like ravens and the great apes, and not because of similar high-level mental faculties as humans, but through associative learning.

- Sir AJ’s Note: This is one point in the semester where we see an interesting point of interface between biology and literature–the way we see Cards/Cognition. ^13f4d0

- While Suvin agrees with the biological perspective on cognition as the ability to perceive reality through logic, he also views ==cognition as an attitude, an approach to reality that views reality as knowable, diametrically opposed to the approach of myth, which views the world’s norms as fixed, mystical, and operating on associative/symbolic logic rather than rationality per se.==

- There’s a lot to be said here about knowledge systems and the way knowledge is constructed and how the rhetoric and language of science has been used to marginalize other systems of knowledge, but I’ll stop here lest we accidentally become an epistemology course.

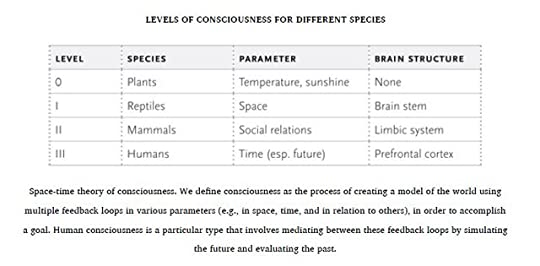

- Consciousness is closely linked to Cards/Cognition. According to the physicist and futurist Michio Kaku in his book The Future of the Mind, Cards/Consciousness is the ability to create a model of the world using multiple feedback loops in different parameters to accomplish goals. The following table shows Kaku’s categorization of levels of consciousness among organisms:

- One can assume that the more primitive vertebrates (fish and amphibians) belong to Level I as well, and birds, which have a well-developed limbic system (that part of the brain that governs emotions, long-term memory, motivation, etc.; the amygdala, which is associated with fear, is part of this system), also are of Level II. Presumably, by Kaku’s categorization, invertebrates lie somewhere between Levels 0 and I, though I would argue that by virtue of their having a centralized nervous system and the ability to move, bilaterally symmetrical invertebrates (basically all invertebrates except sponges, jellyfish, corals, and their radially symmetrical kin) have Level I consciousness.

- The prefrontal cortex is responsible for Cards/Cognition (thus the link between cognition and consciousness!), personality expression, and the moderation of behavior according to social norms (hold onto that; we’ll revisit this when we read and discuss “Love Will Tear Us Apart” in Module 4). Interestingly, the brain part called the Broca’s Area, which is linked to speech production, is associated with the prefrontal cortex.

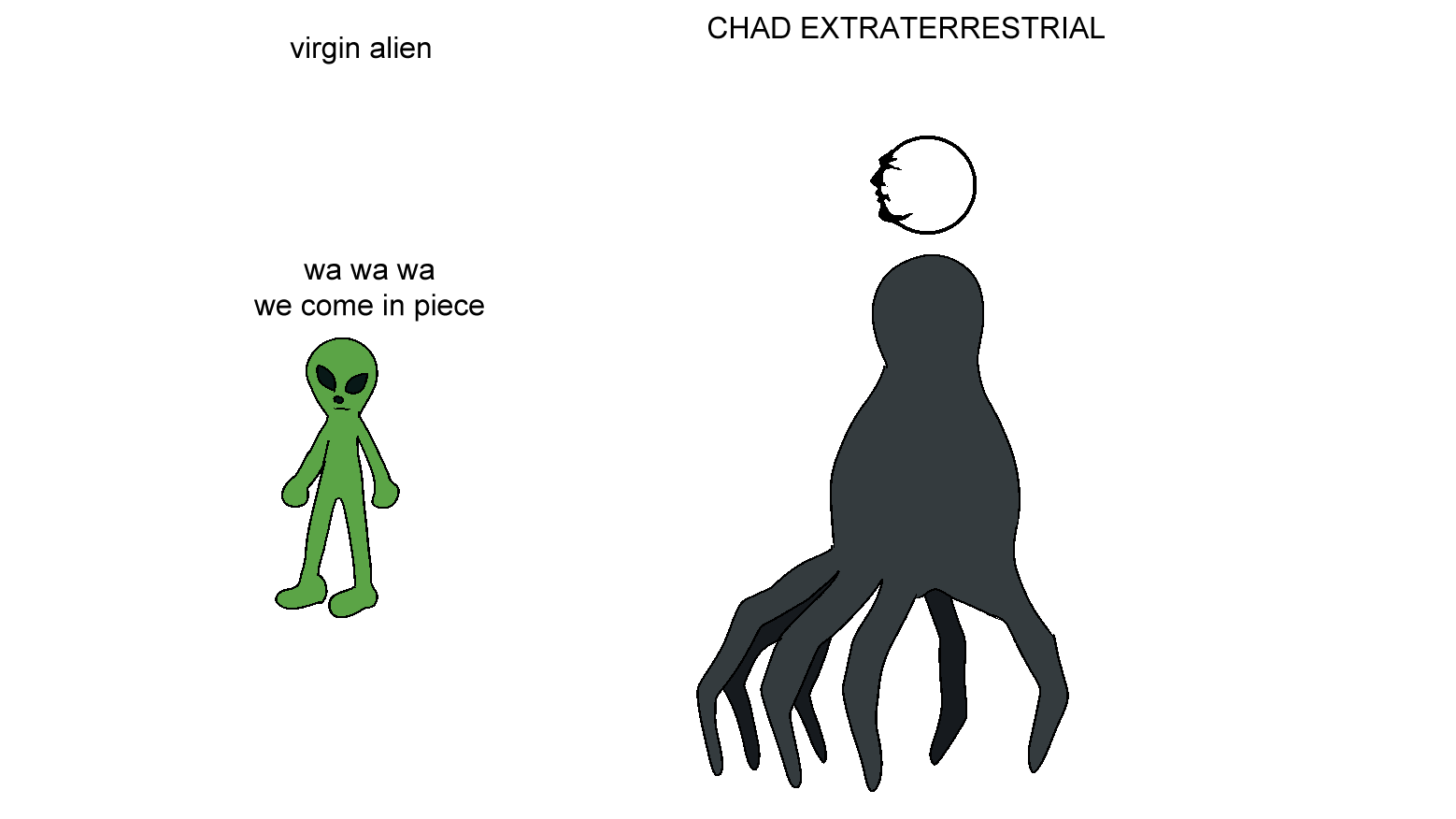

- So if language and cognition are hallmarks of intelligence, then we can say that ==“intelligent species” that are capable of human-like language (like Klingon, for instance) have Level III consciousness…or maybe even higher?== After all, some of the most hyper-intelligent alien species in sci-fi don’t bother to use conventional language as we know it.

- This sets up our first major text for this course, which is the brilliant film Arrival by Denis Villeneuve. Look back at the table and see that the parameter that Level III consciousness has as its playground is time. That’s going to be useful when discussing Arrival’s Heptapods.

# Arrival - The Heptapods

- Arrival revolves around a first-contact scenario, with an enigmatic race of aliens making themselves known to humanity but being nearly impossible to understand, with Adams playing Louise Banks, a linguist recruited by the U.S. military to try to bridge the gap. The heart of the film is ultimately Louise’s struggle to understand and be understood by the aliens, as well as the ripple effects this has on both her own life and the rest of the world’s response to the situation.

- Key to our understanding of Arrival is, of course, the aliens, termed heptapods by the film. The heptapods are mysterious seven-limbed aliens that look like crosses between hovering squid and gigantic hands; they lack facial features, humanity never really comes to understand the sounds they make, and their language consists of circular glyphs of ink projected by the heptapods onto the transparent glasslike walls that separate the heptapods in their ship from the human-safe “guest chamber.” They are, in short, a far cry from the stereotypical greys or little green men of typical science fiction stereotype; the heptapods are well and truly alien, in every sense of the word.

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, the heptapods themselves are the central novum of Arrival; every other science fiction element in the film (their ships, their language, and so on) flows from them. When we read Arrival as a text, therefore, it makes sense that we must look at the design of the heptapods and their related nova in order to begin our reading of what ideas the film is trying to introduce as well as what it is trying to say about these ideas.

Let’s do a little close reading. In the comments section, respond to any of the following questions:

- If we are to look at the heptapods as a sign, what do you think the signified is? What kind of abstract ideas and themes do you think their design is meant to communicate?

- What signifiers do you think Arrival uses to communicate its ideas and themes? What aspects of the design of the heptapods, as well as their ships and language, do you believe are used to communicate the ideas you believe they stand for?

- What can you say about Louise Banks? How do her profession, actions, and overall plot and character arc serve to make a statement about the ideas you believe are signified by the film? Why, of all possible protagonists, is she our hero?

- Discuss the heptapods’ language as its own novum (a novum within a novum!) in the context of semiotics and our discussion in the previous page of language, intelligence, cognition, and consciousness.

# Wonder, Critique, and Possibility

- Science fiction, at its heart, is a genre rooted in ==possibility.==

- That can be hopeful or it can be terrifying–as stated, science fiction is as much about wonder as it is about critique–but ultimately the philosophy that drives it forward is the ==belief that norms are changeable.==

- It is possible to imagine a different universe with its own logic, and it is possible for the logic of a universe to change. Even when history is driven by patterns and cycles, human logic and will and agency have the power to change things, for better or for worse.

- As Suvin writes, “Significant modern SF… discusses primarily the political, psychological, anthropological use and effect of sciences, and philosophy of science, and the becoming or failure of new realities as a result of it.”

- What science fiction seeks, Suvin says, is “a hope of finding[,] in the unknown[,] the ideal environment, tribe, state, intelligence or other aspect of the Supreme Good (or to a fear of and revulsion from its contrary.” It is driven by the belief that ==in confronting the alien, we recognize something–or, conversely, that we can best confront what we know through delving into the unknown. ==

- Frequently that has meant disaster–surely the 2020’s do feel like the right time to take up all sorts of dark literature, be it disaster-driven or dystopian or even apocalyptic. But apocalypse also means ==revelation, the unveiling of a new truth, one that forever changes the old order of things.== (If anyone says the phrase “new normal” to me, I will scream, but you get the idea.)

- And one of the most radical things we can do in a time of crisis is hold onto the hope that there is something new at the end of all this, that hope persists even when we do not see or know it. As Louise Banks reminds us, ==even when we see ruin before us, we can embrace life and try to do what we can until the next thing is revealed.==

- N.K. Jemisin’s 2018 Hugo Awards acceptance speech

- Jemisin reminds us that even in times of hardship, science fiction and fantasy can give us hope: not just the feel-good belief that things can be better, but ==the rigorous work of imagining a different world, and the hard-edged joy of asserting that it can be real.==

- “It’s been a hard year,” Jemisin says, and that was true in 2018 and it’s certainly true now. We hope that your exploration of science fiction, and the work you will put into living this year and beyond, can take something from what she has to share.

- The stars are closer, true believers, and the apocalypse is upon us. Let’s ride.

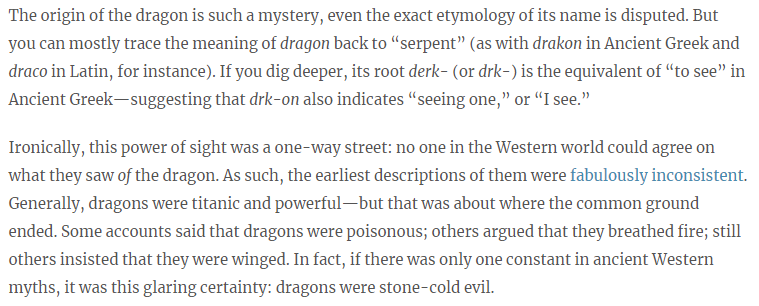

# Creature Spotlight: Here There Be Dragons

This is a part of the course that I’m calling Creature Spotlights. We know our time is limited this quarter, and we didn’t want to overwhelm you with too many texts, but we also wanted the opportunity to discuss some very cool creatures from science fiction that didn’t quite make the cut as full readings. Creature Spotlights are our way of remedying that–a series of quick discussions (**strictly optional–**if you’re low on time, feel free to ignore Creature Spotlights entirely) about iconic or popular science fiction creatures that we can discuss without taking too much time away from the course reading list. And we’re starting here because while this is specifically a science fiction course rather than a broader class on speculative fiction, we would be remiss if we didn’t talk about one of the most iconic creatures in popular culture and mythology: the dragon.

- The dragon’s symbolic power as an exercise in applying semiotics to a fictional creature

- See, the interesting thing about dragons is that while we all more or less know what a dragon is, the image of the dragon has never been entirely constant, instead shifting as one examines different eras and cultures throughout history.

-

“The Evolution of Dragons in Western Literature: A History”

- Early in her article, she lays the foundation for her exploration of the various forms of the dragon with these paragraphs:

- Shiau’s article is a great survey of the various dragon archetypes that have proliferated throughout Western culture and history: she does a good job exploring what the dragon in all its many forms has meant to us. Where she leaves room to speculate is the why of it: why this is the image (or set of images) that has stuck with us and become so iconic and powerful in all our minds.

- Early in her article, she lays the foundation for her exploration of the various forms of the dragon with these paragraphs:

- If you’re interested in learning more about dragons, or want to watch a really cool text that treats a fictional creature as if it were real (what am I talking about, of course dragons are real), you can check out The Last Dragon, one of our suggested readings for the course. It’s a 2004 docufiction film directed by Justin Hardy that examines how dragons might have evolved throughout history if they’d been real. It’s totally optional, but it might be a cool source of inspiration for ways to approach the creative project for this class (and it’s very much in the spirit of what this class is all about).

- But for now, it’s discussion prompt time.

- Choose one of the “major dragons” which Shiau identifies (or some other pop culture dragon that you’d like to talk about). Do some background research on them and expand her brief description of the dragon you picked, paying attention to how they uphold or subvert your expectations of what a dragon is or should be.

- Speculate: what is it about the traits we commonly associate with dragons (e.g. large size, reptilian appearance, supernatural breath weapon, and so on) that we find so compelling? What is it about dragons that makes them such an enduring symbol?

- Dragons can be good models for understanding the basic concepts of evolutionary biology. Why do you think so? Biologically speaking, what make/s dragons a fun exercise in speculative biology (i.e. studying the biology of fictional creatures)?

# Synchronous Lecture Notes

# The Literature of Cognitive Estrangement

- “SF takes off from a fictional (’literary’) hypothesis and develops it with extrapolating and totalizing (‘scientific’) rigor.”

- “The effect of such factual reporting of fictions is one of confronting a set normative system…with a point of view or glance implying a new set of norms.”

- “A representation which estranges is one which allows us to recognize its subject, but at the same time makes it seem unfamiliar.” (Brecht)

# The Novum

- Latin: “new” or “new thing” (in Suvin’s essay, “a strange newness”)

- A novum is a point of difference between the science fiction text and the empirical environment/the real world.

- “An SF text may be based on one novum… [but] more usually it will be predicated on a number of interrelated nova.”

- Suvin posits “a spectrum… running from the idal extreme of exact recreation of the author’s empirical environment to exclusive interest in [the novum].”

- E.G. magical realism v.s. X-Men?

# Science Fiction as Creative Cognition

- “SF is then a literary genre whose necessayr and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment.”

- E.G. biology cells -> zombies

- “For somebody to see all normal happens in a dubious light, he would ned to develop [a detached eye]… It implies a creative approach tending toward a dynamic transformation rather than toward a static mirroring of the author’s environment.”

- E.G. seeing cancer cells as tragic enemies in Cells at Work

- “Such typical methodology of SF…is a critical one, often satirical, combining a belief in the potentialities of reason with methodical doubt.”

# Interlude: Semiotics 101

- Semiotics (n): the study of signs and meaning-making

- From Greek semeiotikos, “observant of signs”

- Sign (n): something that attempts to communicate meaning beyond its literal appearance

- See Miscellaneous Notes/Daily Notes/2022-06-27

# Relationships with Other Genres

- Science fiction has roots in “blessed island” stories (Greek/Hellenistic), the “fabulous voyage” (Antiquity on), “utopia” and “planetary novel” stories (Baroque/Renaissance), the state/political novel (Enlightenment), “anti-utopia” and “anticipation” stories (modern), etc.

- “SF shares with myth, fantasy, fairy tale, and pastoral an opposition to naturalistic or empiricist literary genres” but “differs… in approach and social function.”

- “The myth is diametrically opposed to the cognitive approach since it conceives human relations as fixed, and supernaturally determined.”

- “SF sees the norms of any age, including emphatically its own, as unique, changeable, and therefore subject to cognitive glance.”

- “Where the myth claims to explain once and for all the essence of phenomena, SF posits them first as problems and then explores where they lead to; it sees the mythical static identity as an illusion.”

# Wonder, Critique, and Possibility

- “Significant modern SF…discusses primarily the political, psychological, anthropological use and effect of sciences, and philosophy of science, and the becoming or failure of new realities as a result of it.”

- E.G. Black Mirror’s Nosedive

- “This genre has always been wedded to a hope of finding[,] in the unknown[,] the ideal environment, tribe, state, intelligence or other aspect of the Supreme Good (or to a fear and revulsion from its contrary).”

- “I look to science fiction and fantasy as the ==aspirational drive of the Zeitgeist==: we creators are the engineers of posibility. And as this genre finally, however grudgingly, acknowledges that the dreams of the marginalized matter and that all of us have a future, so will go the world.” (Jemisin, 2018)